Hugh Dowding's Air Defense Revolution

Heretical thinking and a cutting-edge system proved the bomber won't always get through.

Yoel Margolis is a Deployment Strategist intern at Palantir Technologies and a student at Reichman University in Israel.

Less than a month after the fall of France, the German Luftwaffe set its sights on Britain, launching near-daily bomber raids to achieve air superiority in preparation for invasion. Many of those raids failed. Formations of Royal Air Force (RAF) Spitfires and Hurricanes pounced on German bombers, almost as if they were waiting for their arrival. The German crews were dumbfounded. How did the British pilots know their exact position with such remarkable accuracy?

The answer was the Dowding System, a complex organization of detection, command, and control centers that is credited as the world’s first integrated air defense system. To understand just how innovative this network was, one must remember that “range and direction finding”—the British precursor to radar and the technological foundation of the system—was no more than five years old in the summer of 1940.

The mastermind (and eponym) of the Dowding System was Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, the 54-year-old head of RAF Fighter Command. How was Dowding rewarded for designing and commanding the system that successfully defended Britain from Hitler’s Luftwaffe? With forced retirement and a long list of enemies in the RAF senior leadership and British War Cabinet.

Dowding was an unlikely heretic, neither combative nor overbearing (unlike many others in this series). He was a reserved operator, arguing with colleagues only when he deemed it absolutely necessary. No one doubted his intentions or commitment to British military interests. Yet, he was removed from his command just months after the Blitz.

Dowding’s story offers practical lessons about integrating modern technologies into complex military systems. Perhaps more important, his story is a lasting reminder that success depends not only on innovation, but on the courage to challenge the institutions that fear it most.

The Bomber Will Not Always Get Through

British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin declared in 1932 that “the bomber will always get through.” This assertion expressed deep-seated fears about strategic bombing that emerged during the First World War and intensified in the years that followed, as aircraft performance and payloads increased.

Marshal Hugh Trenchard, commander of the RAF, believed the answer to this threat was offensive buildup: creating bomber forces that could rival those of any enemy. Trenchard’s tendency to promote like-minded officers led to the RAF’s domination during the interwar years by what became known as the “bomber cult.”

Dowding, characteristically skeptical and contrarian, questioned the pervasive defeatism. He argued that instead of maximizing offensive capabilities, the proper strategy was defensive—emphasizing the development of fighters over bombers and exploring the potential use of emerging technologies to assist in early detection and warning.

This was not Dowding’s first disagreement with RAF superiors. In 1905, the Wright Brothers had pitched their newly invented airplane to the British army after being turned down by the Royal Navy. The army likewise declined; the responsible officers responded after a presentation on the aircraft’s potential reconnaissance capabilities that “aircraft could not fly at less than forty miles per hour, and it would be impossible for anyone to see anything of value at that rather high speed.”

Dowding, upon learning of the new invention, thought otherwise. Then a young officer in the Royal Garrison Artillery, he proposed using aircraft as a reconnaissance tool in a training exercise. His commanding officer dismissed the idea with laughter, predicting certain failure. Instead, Dowding’s six planes provided precise intelligence on enemy positions from unprecedented distances, enabling his decisive victory in the drill.

Twenty-five years later, while exploring technologies to support his defensive strategy, Dowding came across another intriguing invention. In 1935, radio engineer Robert Watson-Watt published a memo for the Air Ministry relating how overflying aircraft disrupted radio waves. He proposed that such disruptions could form the basis for aircraft detection and location. Dowding, in his role as Air Member for Supply and Research—a position which gave him oversight over scientific research within the RAF—, saw in these findings a potential solution for his dream of an air defense system. He enthusiastically provided the funding for further research.

This decision was controversial. Many in the RAF, especially members of the bomber cult, were skeptical of what became known as range and direction finding technology. Nevertheless, Dowding embraced the idea and championed its research all the way through its eventual integration in his grand air defense system.

Fighter Command

In 1936, with war on the horizon, Dowding was given control of the newly formed Fighter Command. He immediately went to work pushing for his contrarian, defensive approach. As Dowding saw it, the key to a successful defense was a strong fleet of fighters and well-trained pilots. Even the best warning system would be worthless without fighters to intercept incoming bomber formations.

Dowding shared this notion with another Heretic and Hero: Lord Beaverbrook. Their relationship was close. The two spoke almost daily to collaborate on their joint mission of increasing fighter production before the war began.

With the invasion of France in the summer of 1940, Dowding’s most intense bureaucratic battle began. Shocked by the invasion, British cabinet officials—up to and including Churchill—immediately responded to urgent French requests by sending fighter squadrons across the Channel to aid in the defensive campaign against the Germans. Dowding, worried about a shortage of fighters for home defense, bitterly opposed these transfers. This opinion brought him into direct confrontation with Churchill, usually sympathetic to Dowding. In May of 1940, Churchill requested six additional squadrons to send to France. The cabinet, successfully persuaded by Dowding’s lobbying, refused the request. This move proved monumentally significant in light of the Fall of France just one month later. Historians generally agree that sending the fighters would likely have had no effect in preventing the fall but would have significantly weakened British preparedness for the eventual assault on the homeland.

The Dowding System

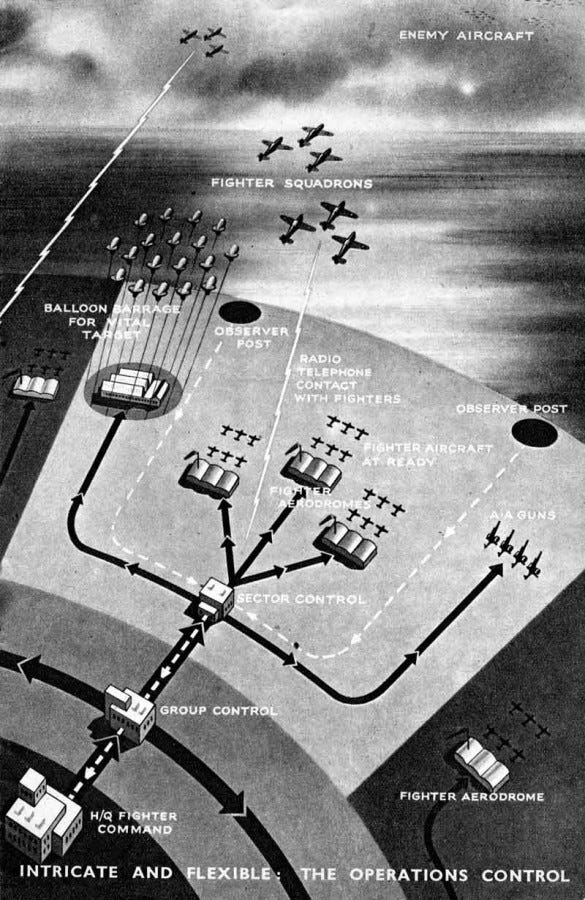

Dowding’s insistence on keeping fighters in Britain proved prescient when the Luftwaffe turned its attention to the home islands. Britain had the fighters Dowding needed to implement his revolutionary detection and command system. The Dowding System combined cutting-edge radar, streamlined communications networks, and overlapping redundancies to detect incoming aircraft, track their precise locations, and direct RAF fighters to intercept them. To do so, the system had to overcome several immense challenges.

1. Lack of Early Detection.

All earlier methods of aircraft detection relied on human observation or acoustic mirroring. These approaches had extremely short ranges (sometimes as little as five miles). By the time an incoming aircraft was detected and the information was processed, the bomber would likely have reached its target, leaving no time for fighters to scramble and engage.

To solve for early detection, Dowding, relying on newly developed range and direction finding technology, established the Chain Home network, a system of linked RDF stations along the British coast. Each station provided aircraft detection coverage extending 60 to 100 miles over water within their assigned zones.

To cover for breaches in Chain Home, an additional network called Chain Home Low was established with specialized RDF stations capable of detecting aircraft flying at low altitudes. Finally, a volunteer Observer Corps was organized to provide inland detection capabilities, addressing the primary limitation of both Chain Home networks: their inability to track aircraft once they moved over land.

2. Information Overload

RDF stations generated massive amounts of data, with enemy aircraft often reported by multiple stations at slightly different times, creating a data stream that was very difficult to manage in a pre-computer era.

Dowding solved this problem by implementing a hierarchical command-and-control network. All reports of incoming aircraft were routed to a single Filter Centre, where operators plotted aircraft locations onto a table-size map called the Recognized Air Picture (RAP).

This near-instantaneous intelligence was then disseminated to one of four Group Headquarters, charged with creating their own intelligence picture for a particular area. The Group Headquarter in turn forwarded the information to the airfield-based Sector Commands Centers that communicated directly with the pilots.

Consequently, pilots received only the most up-to-date, mission-specific information. All language was standardized across the entire RAF, allowing squadrons and pilots to be moved between groups or sectors without learning new vernacular.

3. Inefficient Use of Resources

Prior to the development of a combined network, air defense depended on fighter patrols flying along predetermined paths in the hope of encountering the enemy. This method was incredibly inefficient, with very low interception rates.

Dowding’s solution increased the efficiency of the RAF’s resources dramatically. By providing precise information on the location of enemy aircraft, commanders could wait until an incursion was reported before deploying their fighters, ensuring they were not needlessly airborne. Furthermore, the overlap of the two Chain Home networks, combined with the Observer Corp, ensured that the surveillance coverage was complete.

Opposition

Dowding’s system and his leadership of Fighter Command played a crucial role in thwarting Hitler’s plans for air domination of Britain. However, the very strategy that saved Britain also threatened the reputations of those who had built their authority on the belief of bomber invincibility. The strongest resistance to Dowding came from within the RAF, and largely revolved around his insistence on resource conservation. Dowding was adamant that Britain’s goal was singular: survival. As such, he believed in conserving fighters, relying on precise vectoring to send a smaller number of fighters to confront incoming bombers.

A faction within the RAF disagreed with Dowding’s approach. Known as the Big Wing group, it advocated for large formations of fighters (Big Wings) to attack the enemy en masse.

Leading this faction was Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh Mallory, commander of No. 12 Group, who vowed to “move heaven and earth to get Dowding sacked.” He succeeded through ambush, luring Dowding into a meeting with some his biggest enemies, in which Dowding was accused of mishandling the Battle of Britain.

Their argument rested largely on the claim that the Dowding system’s nighttime performance was significantly worse than its daytime effectiveness. The heavy reliance on the Observer Corps for visual confirmation, they contended, combined with the bottleneck of a single filtering center, made nighttime raids considerably more difficult to intercept.

Dowding remained steadfast in defending his hierarchical filtering system. He and his supporters maintained that the current system was essential for correctly identifying enemy aircraft. They believed that with greater innovation—particularly in radar technology—nighttime capabilities would improve.

Nevertheless, the Big Wing faction ultimately prevailed, and in November 1940, Dowding was removed from his position as head of Fighter Command. Despite the official rationale for his firing, many argue that Dowding’s real offense was that he had disproved the RAF and the government’s fundamental belief that bombers were unstoppable.

Following his dismissal, Dowding was sent to Washington to lead the British Air Mission to the United States. However, in 1942, frustrated at the lack of appreciation for his historic contributions, he retired from the RAF.

His frustration persisted through retirement. Though he was raised to the peerage and created 1st Baron Dowding, the Air Ministry passed him over for the honorary title of Marshal of the Royal Air Force. In 1969, he supported the publication of a book by the historian Robert Wright that explicitly attributed his dismissal to a conspiracy orchestrated by Big Wing supporters.

In recent years, history has begun to treat him more favorably. Most historians today concur that Dowding’s system and leadership were decisive to British success in the Battle of Britain.

Tragically, Dowding never lived to witness his vindication. He died in 1970, still convinced he had been treated unjustly by the organization to which he had dedicated his life.

Legacy

Eighty-five years after the Blitz, Dowding’s story offers enduring lessons for modern defense.

Every generation confronts its equivalent of “the bomber will always get through” fatalism. Today’s version may be defeatism surrounding the application of AI in defense or the cost asymmetry in drone warfare. Dowding’s strength lay in rejecting both fatalism and denial, acknowledging potential dangers while acting pragmatically to counter them. His resistance to dogma came from his practical approach to problem solving, not an inherently rebellious nature.

Additionally, Dowding teaches us that revolutionary technology is important but insufficient on its own. The Battle of Britain was not won because the British possessed radar. It was won because they had the Dowding System—a masterfully designed internal infrastructure that successfully merged the human components of the RAF with the deployment of radar and other innovations.

Most poignantly, Dowding’s rise and fall exemplifies the immense challenges and potential consequences of righteous heresy within military bureaucracies. His dismissal just months after victory stands as a stark reminder of the costs of being right—a burden all heretics bear, if not always to the same extreme. One hopes that future leaders will possess Dowding’s conviction to challenge orthodoxies and drive change despite inevitable resistance.