Lord Beaverbrook’s Production Magic

Forceful leadership, media savvy supercharged Spitfire production and won the Battle of Britain.

Austin Gray is Co-Founder and CSO of Blue Water Autonomy, a defense tech shipbuilder. He writes frequently on Not Those Shades of Gray, where he’ll soon have more analysis of WW2 production lessons, from Spitfires to ships. He previously worked in a drone factory in Ukraine and served on active duty as a naval intelligence officer. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and holds degrees from Davidson, MIT, and Harvard.

As the Luftwaffe massed across the English Channel in the summer of 1940, Britain’s great hope was the Spitfire. Elegant, fast, deadly—but barely available. When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Britain was producing just 13 Spitfires per month. By September 1939, when Britain and France declared war on Germany, British factories were producing 32 Spitfires per month.

They needed far more. Fighting over Flanders and France in early 1940 sacrificed 458 British aircraft. Germany, capable of producing more than 900 aircraft per month, could afford such losses. Britain could not. The Air Ministry knew it needed to ramp production. But the gigafactory that was supposed to churn them out, Castle Bromwich near Birmingham, had become a national embarrassment. Britain’s Spitfire production had stalled at its most critical hour.

Lord Nuffield, the automobile magnate tasked with running this new factory, had promised 240 Spitfires per month by May 1940. Instead, he delivered chaos. Castle Bromwich had not yet delivered a single Spitfire. Workers lacked training. Jigs and tools were missing. Subcontractors were late. The factory resembled a derelict workshop, not a humming factory organized by an experienced titan of industry. With the Battle of Britain beginning, the Royal Air Force (RAF) needed Castle Bromwich’s capacity.

Enter Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian press baron whom Churchill appointed Minister of Aircraft Production on May 14, 1940. Beaverbrook saw the disaster at Castle Bromwich and knew that Britain’s survival depended on his ability to turn around the plant.

He phoned Nuffield, stripped him of control, and handed the plant to Edward ‘Rex’ Talamo, a mustached optimist who would bet Beaverbrook 500 guineas he could double production. He imported seasoned managers from Spitfire producer Supermarine, imposed his own frenetic style of oversight, and demanded daily output figures.

The effect was immediate. In June 1940, Castle Bromwich delivered its first 10 Spitfires. In July, 23 more. By August, 37. By September, 56—just in time for the Battle of Britain’s peak. Within a year, Castle Bromwich was the largest Spitfire producer in the country, eventually turning out more than 12,000 aircraft. Churchill was so happy with the turnaround that he sent Rex an inscribed silver ash tray and brought the king to tour the factory.

The episode became Beaverbrook’s trademark: find a mess, smash through the polite obstacles, and will results into being. To bureaucrats he was reckless; to production workers he was a savior. And to the RAF pilots flying Castle Bromwich Spitfires in 1940, he was something else entirely: the difference between life and death. Although the Spitfire turnaround captures the essence of his leadership style, Lord Beaverbrook’s duties in wartime Britain extended across multiple ministries and critical assignments. Wherever Churchill needed his focus, wherever Britain needed his energy, Beaverbrook was the man in the breach.

Britain’s Bureaucratic Swamp

To understand Beaverbrook’s impact, we have to appreciate just how messy Britain’s production system was in 1940. We also need to know who Beaverbrook was.

Before Churchill created the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), responsibility for aircraft orders, contracts, and factories was scattered across multiple bodies:

The Air Ministry, which set requirements and specifications but was notorious for delay.

The Ministry of Supply, handling weapons and munitions.

The Ministry of Labour, allocating workers.

Interdepartmental production committees, which produced reports but lacked enforcement power.

In all, Britain’s official history of war production lists 19 different ministries involved in the production of military equipment. [1]

In theory, this distributed system encouraged coordination. In practice, it produced memos, turf wars, and excuses. Aircraft firms complained of shortages of aluminum and machine tools; engine makers blamed subcontractors; the Air Ministry insisted on design changes mid-stream. Meanwhile, frontline squadrons waited for airplanes that never came.

Beaverbrook cut through the bureaucratic briar patch with one heretical act: he centralized power in himself, making every order of raw materials, every workforce shift, and every production target subordinate to the Ministry of Aircraft Production. He ignored committees, bypassed ministries, and worked directly with factory managers. The production of aircraft to defend Britain’s skies was his, his ministry’s, and the government’s highest priority—enforced by sheer force of personality and often at the expense of others.

The Crooked Outsider

Lord Beaverbrook was never a man for staid institutions. Born in Canada by the name Max Aitken, he made his fortune in finance before 30, moved to Britain, and reinvented himself as a newspaper baron. His Daily Express became the highest-circulation paper in the world by appealing directly to mass audiences with speed, spectacle, and sensation.

Whitehall hated him. Too brash, too Canadian, too rich. He dressed down civil servants, scrawled corrections across their reports in red ink, and called the Air Ministry “the Ministry of Obstruction.” The historian Jonathan Schneer writes in Ministers at War: Winston Churchill and His War Cabinet that “Beaverbrook despised committee work, hidebound tradition, red tape and, above all, the time that he judged to be wasted talking,” especially with Royal Air Force generals. Even his allies found him exhausting. Churchill called him “my ferret”—and ferret-like, Beaverbrook burrowed into bureaucratic bottlenecks with manic energy.

Production as Warfighting

Beaverbrook’s genius wasn’t engineering—he didn’t design the Spitfire’s elliptical wing or Rolls-Royce’s Merlin engine. His genius was industrial relentlessness. “Urgency was in his temperament” wrote Schneer, who knew Max personally. His 3 a.m. calls to subordinates and peers infectiously spread that urgency.

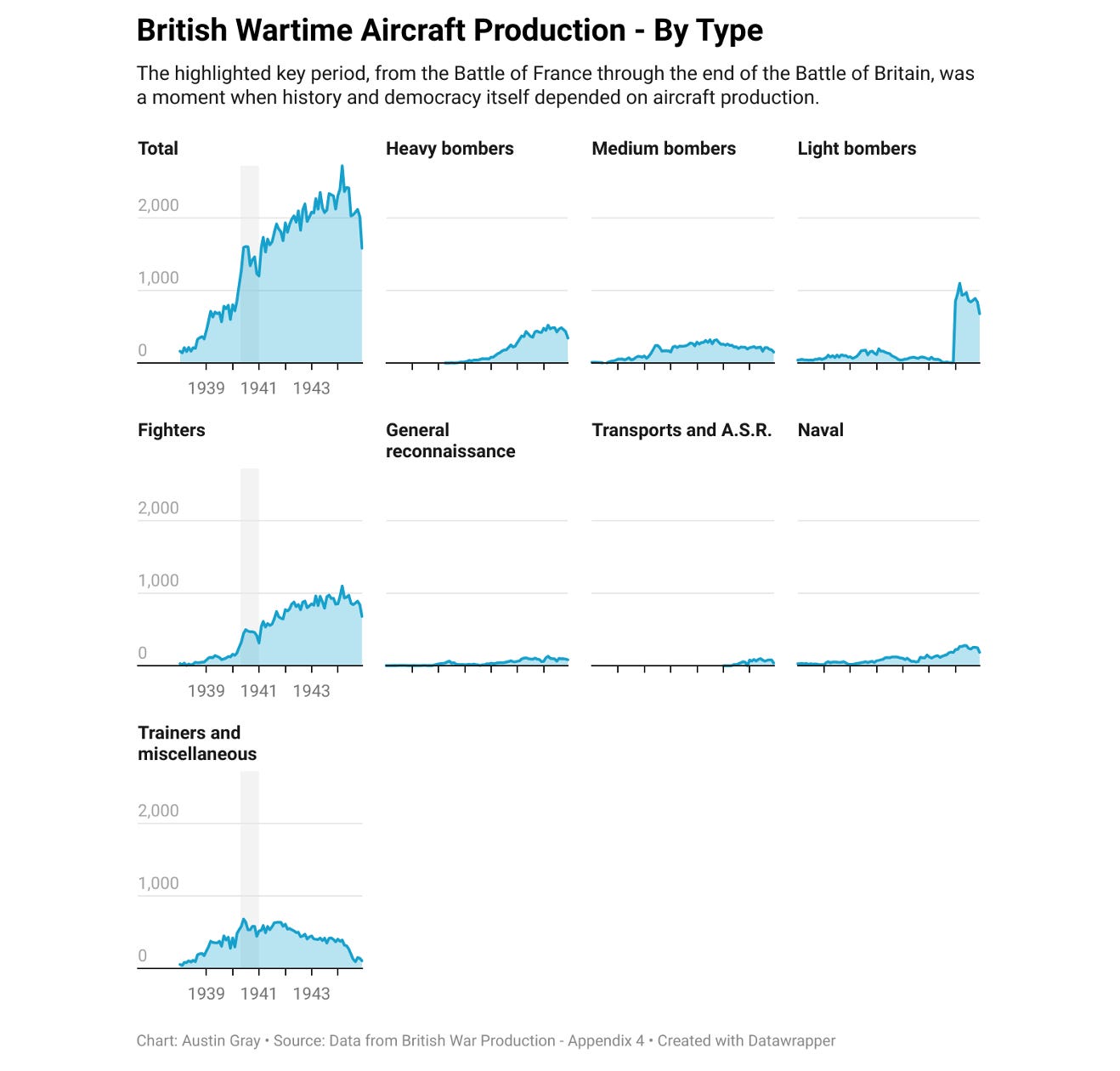

His ability to reprioritize anything was forged in a newspaper culture centered on breaking a story first and printing on time, accurately. As in journalism, second place in war would not suffice. Hurricanes and Spitfires came first. Civilian aircraft programs were scrapped. Bombers were deferred. Trainers and transports were secondary. Every ton of aluminum, every skilled worker, every machine tool went into fighters.

The results were dramatic. In May 1940, Britain built fewer than 300 fighters. By July, that critical monthly figure had nearly doubled. By September, during the height of the Battle of Britain, factories were delivering more aircraft than Fighter Command was losing. Production had outpaced attrition, giving Britain the razor’s edge margin to avert defeat. By summer’s end, Churchill summed up Beaverbrook’s turnaround “magic” in classic, emphatic commentary before Parliament:

At the same time the splendid, nay, astounding increase in the output and repair of British aircraft and engines which Lord Beaverbrook has achieved by a genius of organisation and drive, which looks like magic, has given us overflowing reserves of every type of aircraft, and an ever mounting stream of production both in quantity and quality. The enemy is, of course, far more numerous than we are. But our new production already, as I am advised, largely exceeds his, and the American production is only just beginning to flow in. It is a fact, as I see from my daily returns, that our bomber and fighter strengths now, after all this fighting, are larger than they have ever been.

But Beaverbrook didn’t just juggle numbers; he understood psychology. He plastered factory walls with production tallies. He encouraged managers to publish subassembly competitions between shops (across the Atlantic, Henry Kaiser’s shipyards held similar competitions). He told women in factories that they were just as important as men in cockpits. Then, using his Daily Express network, he broadcast the message nationwide.

He made riveters and machinists feel like warriors—and they started to perform like industrial gladiators.

Methods of a Heretic

Beaverbrook’s approach was unorthodox, often destructive, but uniquely suited to the crisis:

Bulldozing bureaucracy. “Beaverbrook smashed all the old bottlenecks and obstacles to rapid production,” wrote Jonathan Schneer in Ministers at War. He ripped authority away from committees and centralized it in himself. When Air Ministry officials protested, he ignored them.

Short-term obsession. He focused relentlessly on output this week, this month. Critics said he sacrificed long-term planning—and he did. But in 1940, survival mattered more than sustainability.

Publicity as a weapon. He used his press empire to glorify successful factories and shame laggards.

Crisis leadership. “The man for the moment, not for the hour,” wrote Schneer, articulating that Beaverbrook was not the perfect leader for all seasons. “When the danger of imminent German invasion lapsed, and when he really could no longer stand the paperwork and committee work any longer, he resigned.”

Even the official history drily observes that Beaverbrook’s authority was personal, rather than institutional. The Ministry for Aircraft Production worked because Beaverbrook bent it to his will. When he faced opponents in the bureaucracy, they knew he had a direct line to Churchill, an old and trusted friend from before his time in government. When he left in 1941, his successors never replicated his energy.

Of course, miracles often come at a cost. Beaverbrook’s short-termism starved bomber production just as the RAF was preparing its strategic offensive. The prioritization system he introduced had so few priorities that essentials like ammunition, tanks, and artillery did not make the initial list. His endless feuds alienated colleagues doing their duty on other government work. And his pace was unsustainable: after less than a year at the ministry, he resigned, citing exhaustion.

Even Churchill, who valued him above almost anyone in the cabinet and knew he was the best man in a crisis, admitted that Beaverbrook had rough edges.

Hero After All

Yet the verdict of history is clear. Without Beaverbrook, the Battle of Britain may have been Britain’s final battle. Fighter Command might have run out of aircraft in 1940. The RAF might have lost the skies. And Britain might have lost the war.

In The Splendid and the Vile, Erik Larson portrays him as manic, restless, nearly unhinged. In British War Production, he comes across as blunt and unsustainable. In Ministers at War, he is indispensable. Each portrait is true. Lord Beaverbrook was a heretic—but in Britain’s darkest hour, his heresy was precisely what was required.

And Beaverbrook wasn’t a natural choice for Churchill. Although they were old friends, Beaverbrook had supported Chamberlain and a negotiated settlement with Germany. He also had no experience in high government office, having only briefly served in Parliament decades before. King George himself noted these reservations to Churchill upon learning of the intended appointment.

Beaverbrook didn’t stop with aircraft production. He went on to lead the Ministry of Supply, which was to the Army what the Ministry for Aircraft Production was to the Air Force. Then, when Churchill needed a joint Ministry of Production to coordinate industrial policy with Soviet and American peers, he briefly served as the first minister.

Lessons for Today: Munitions, Shipbuilding, and Deterrence in the Pacific

For today’s defense technologists and acquisition leaders, the lesson is pointed. In times of disruption, processes and committees can become fatal luxuries. Sometimes survival depends on heresy—on giving one frenetic outsider the power to cut through the system and deliver what the moment demands.

More tactically, political leaders building their executive teams need strong, empowered lieutenants—men and women who can bring outside perspective and credibility to government institutions, but still operate with speed and precision inside the complex reality of government. These leaders must step away from rewarding careers, and, along with their families, endure the costs of entering the political arena. Changemakers like Lord Beaverbrook must be ready to make enemies and face vicious attacks in the press. And in a hyper-political era, they must wield the press, feeding their wins into the national discourse to fuel their own political power.

Today, as in 1940, critical military production is stalling. China’s fleet of warships grows while the U.S. fleet shrinks. U.S. missile and artillery stocks are dwindling, with production rates creeping up too slowly. With such trends, People’s Liberation Army commanders may gamble that their American counterparts won’t risk a force they can’t regenerate.

Might deterrence in the Pacific be saved by a 21st century Beaverbrook?

[1] As a bonus, here’s a list of all 19 ministries involved in the production of British military equipment and a quick explanation of their duties:

Aircraft Production (MAP) – Directed the design, production, and allocation of aircraft.

Agriculture and Fisheries – Oversaw food production and farm supply mobilization.

Blockade – Managed economic warfare and control of enemy trade access.

Economic Warfare – Coordinated with Allies on blockade and enemy trade disruption.

Food – Managed rationing, food distribution, and imports.

Health – Maintained civilian medical services and public health.

Home Security – Coordinated civil defense and air raid precautions.

Information – Handled propaganda, news, and public information.

Labour and National Service – Controlled manpower allocation, conscription, and labor disputes.

Production – Managed raw material allocation and general war industry production.

Shipping – Oversaw merchant fleet, convoys, and shipping priorities.

Supply – Coordinated allocation of weapons, munitions, and raw materials.

Transport – Managed railways, road transport, and fuel allocation.

War Transport – Integrated civilian and military transport coordination.

War – Directed the British Army and ground force operations.

Works – Managed construction, repair, and airfield/building projects.

Board of Trade – Regulated trade, industry, and economic policy.

Treasury – Controlled finance, budgets, and economic mobilization.

Air – Directed the Royal Air Force (operations, not production).