Winston Churchill and His Majesty’s Landships

When the Royal Navy built a tank for the British Army

First Breakfast exists to wage war on complacency and inspire action. The Arsenal of Democracy is broken. The cupboard is bare. It will take men and women of singular vision and drive to fix these problems. It always has.

We want to celebrate the heroes whose “blood, toil, tears, and sweat” saw us through past crises. This series is dedicated to “the crazy ones” who took on the bureaucracy, built new things, and brought victory to past battlefields, on wings, wheels, and tracks. We hope it inspires new leaders to roll up their sleeves, buck convention, and build what’s needed to win again.

A young Winston Churchill realized that war was changing when, in 1898, he saw a British and Egyptian force under Horatio Kitchener decimate the ranks of a charging Islamist army with Maxim guns. He assumed tactics would change, as well. “This is the end of these sort of spectacles,” he thought afterward. “There will never be such fools in the world again.”

Churchill was wrong about that.

By late 1914, trenches and shell craters marred the fields of France. Machine guns and artillery inflicted dreadful casualties. Yet frontal assaults continued, carried out by the very armies that had introduced the machine gun decades before.

British leaders suddenly were confronted with total war and their unpreparedness for it. They hadn’t invested in armor. Years earlier, one of the only British companies developing tracked vehicles sold its patent to an American company that would one day become Caterpillar; Britain had to buy back its own technology when the war began. The British military also neglected munitions, leading to “shell famine.” (If this sounds eerily similar to modern headlines, it should.) British soldiers were thrown into frontal assaults with no protection and little supporting artillery to soften the defenses. The results were horrible, if predictable.

Churchill threw his all into solving the problem of trench warfare. If not him, who? Brass on both sides, he was convinced, were captives of events instead of their authors. They obsessed over gains measured in yards instead of planning for breakthrough and victory. And they were hostile to change. “Men held in the grip of discipline, moving perilously from fact to fact, are nearly always opposed to new ideas,” he wrote. Churchill wanted to break out of this paradigm. “Let them [the Germans] rejoice in the occasional capture of placeless names and sterile ridges; & let us dart here & there armed with science and surprise.”

The only problem? Churchill worked for the Admiralty, not the Army. He was supposed to be directing the fight on the waves, not the Western front. To Churchill, this was a technicality rather than a restraint. The fighting was on land. That’s where he would direct his efforts.

At war’s outset, Churchill therefore hatched a number of schemes to get the Navy in the fight. He plotted a daring amphibious landing to seize the Dardanelles Strait and open a new front. (This would not go well). He also landed Royal Marines in the Low Country, first as a diversion and then to protect naval airfields on the Continent.

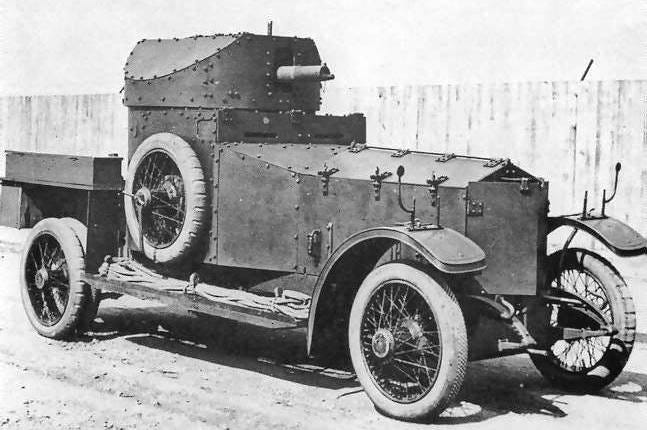

Over time Churchill’s detachment became more like a marauding force. While small in numbers, it punched above its weight in technology and elan. Its members strapped Maxim guns and plate armor to Rolls-Royces and tore through the European countryside harassing the enemy.

“Winston’s circus,” as it became known, was not universally loved. The Army chafed at the Navy’s encroachment. Kitchener, now Secretary of War, derided the armored car squadron as an “irregular detachment” and complained about it to Churchill in a series of increasingly testy letters. The Sea Lords of the Admiralty were similarly closed-minded. “Motor cars have nothing to do with the Naval Service,” remarked one.

By 1915, the war and Churchill’s armored cars had bogged down in mud. It was time to pivot. But he didn’t abandon his vision of a siege-breaking machine. Crossing No Man’s Land, he wrote, “ought not to be beyond the range of modern science if sufficient authority had backed the investigation.” He knew it was possible. So he seized the initiative.

Acting in secret, Churchill formed a “Landship Committee.” To pay for it, he diverted money from an Admiralty fund for auxiliary machines. He put in charge Eustace D’Eyncourt, Director of Naval Construction, who had previously designed battleships and airships. And he brought in madcap talent like Thomas Heatherington, an armored-car driver with visions of wheeled machines as big as Ferris wheels.

This was a motley crew, but it had the advantage of being the only game in town.

There were many false starts. No one had built a “landship” before, so no one knew the specs. The committee divided over whether the machine should be tracked, wheeled, or something else entirely. Churchill favored large steamrollers to “crush” trenches. But despite his stubbornness, he proved able to abandon ideas when they proved impractical, as with the roller.

By a process of trial and error, working on a shoestring budget, the landships took form. A tractor was procured from the United States and demonstrated before Churchill and David Lloyd George, the Munitions Minister. Its success influenced the adoption of chain traction as the method of propulsion for subsequent tanks. Churchill goaded the team with relentless, terse messages at every step: “Press on”; “Proceed as proposed and with all dispatch.”

Disaster struck in late 1915, as the Landship Committee was closing in on prototypes. The Dardanelle campaign had turned into a debacle. Churchill took the fall and resigned. The Admiralty was only too happy to be rid of “Winston’s fad,” as his successor called it. But by that point the war was going so poorly that the Army bowed to the need for fresh thinking. It agreed to a joint project to develop landships. Finally, the project was given the resources and urgency it deserved.

In January 1916, the first Mark 1 tank, christened “His Majesty’s Land Ship Centipede,” went through trials in Hatfield Park, to great success. Kitchener was on hand, but remained skeptical to the last. He left early, dismissing it as a “pretty mechanical toy.” Lloyd George saw more promise in the machine. He ordered 100.

Churchill was not at the trials. He was dodging shells on the Western Front, experiencing firsthand the consequences of small thinking and inaction. He heard about them afterward in a letter from D’Eyncourt, who reported the landship had torn through wire “like a rhinoceros through a field of corn.”

This must have been vindicating, like the events that followed. The tank first saw action eight months later, and proved decisive at the Battle of Cambrai. Churchill exulted. “The Goddess of Surprise had at last returned to the Western Front,” he recalled.

A royal commission established after the war to reward inventors credited Churchill’s “receptivity, courage, and driving force” for helping the tank take on practical form.

It took the Royal Navy—or at least a secret part of it—to build the tank for the British Army. It took a leader of irrepressible vision and enthusiasm to deliver the technology that broke the trenches in the Great War.

Further Reading

The World Crisis by Winston Churchill

The Devil’s Chariots: The Birth and Secret Battles of the First Tanks by John Glanfield