The Unlikely Team That Built an Ironclad and Saved the Union

A disgraced engineer, a young financier, and a risk-taking bureaucrat can teach us about defense innovation.

Scarlett Swerdlow is a product manager at Orbis Operations. She served as a Digital Service Expert in the U.S. Department of Defense, where she helped digitize the world’s largest collection of human tissue samples, improve the drone defenses of American military bases in the Middle East, and reduce interruptions to the DOD Information Network. Outside of work, Scarlett loves visiting Civil War battlefields, creating Taylor Swift data visualizations, and traveling in search of the world’s best food.

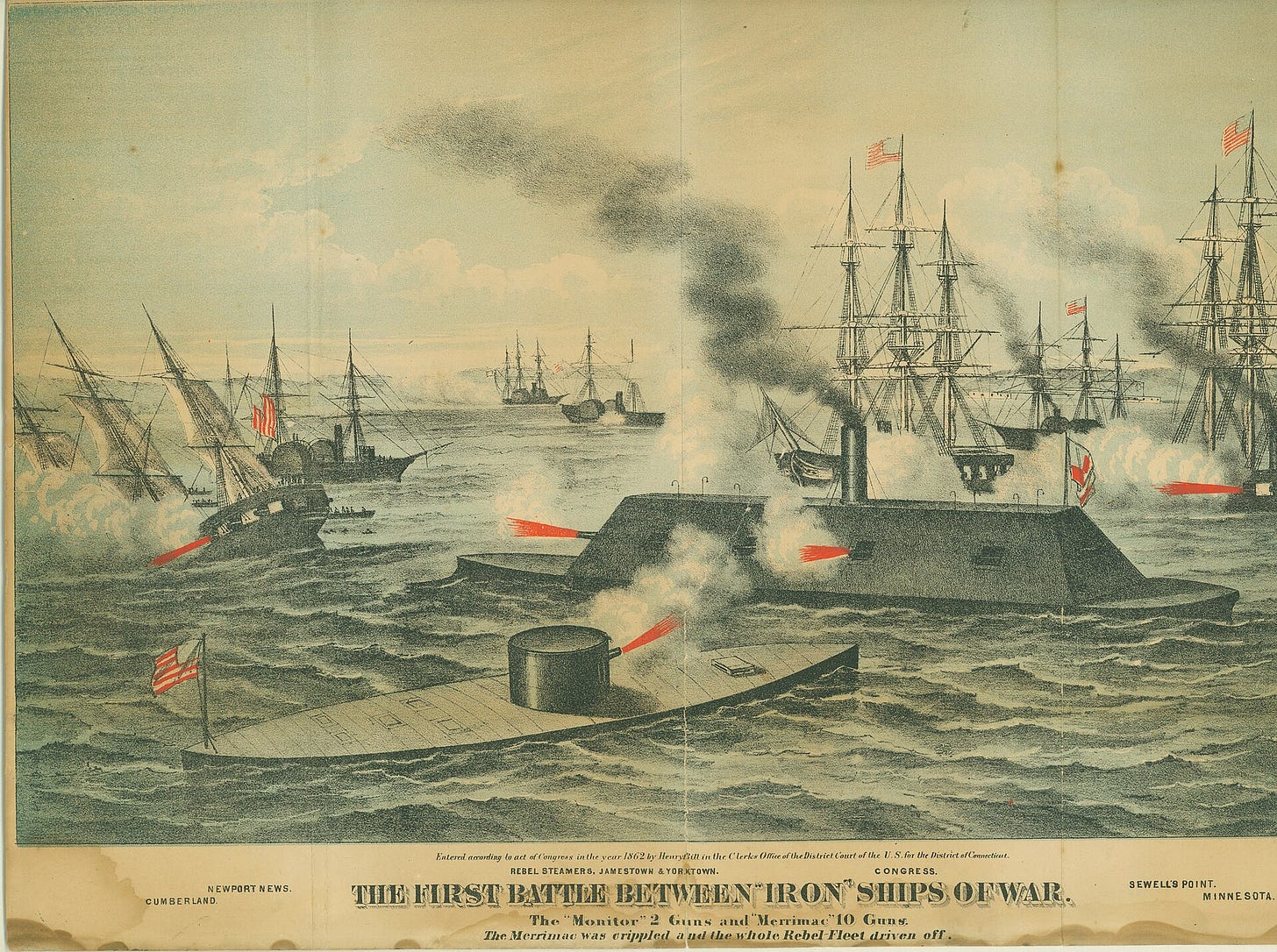

On the morning of March 8, 1862, the CSS Virginia steamed into Hampton Roads and announced the future of naval warfare. Built from the wreckage of the USS Merrimack and armored with iron plate, the Confederate ironclad devastated the Union’s wooden fleet. It rammed and sank the USS Cumberland, then turned its guns on the USS Congress until it surrendered and burned. Only nightfall and the ebbing tide saved the grounded USS Minnesota. By day’s end, 261 Union sailors were dead and another 108 wounded. It was the worst day for the U.S. Navy until Pearl Harbor.

That night, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton predicted catastrophe. According to witnesses, he panicked that the Virginia “would destroy every vessel in the service, could lay every city on the coast under contribution . . . likely [its] first movement would be to come up the Potomac and disperse Congress, destroy the Capitol and public buildings; or she might go to New York and Boston and destroy those cities.”

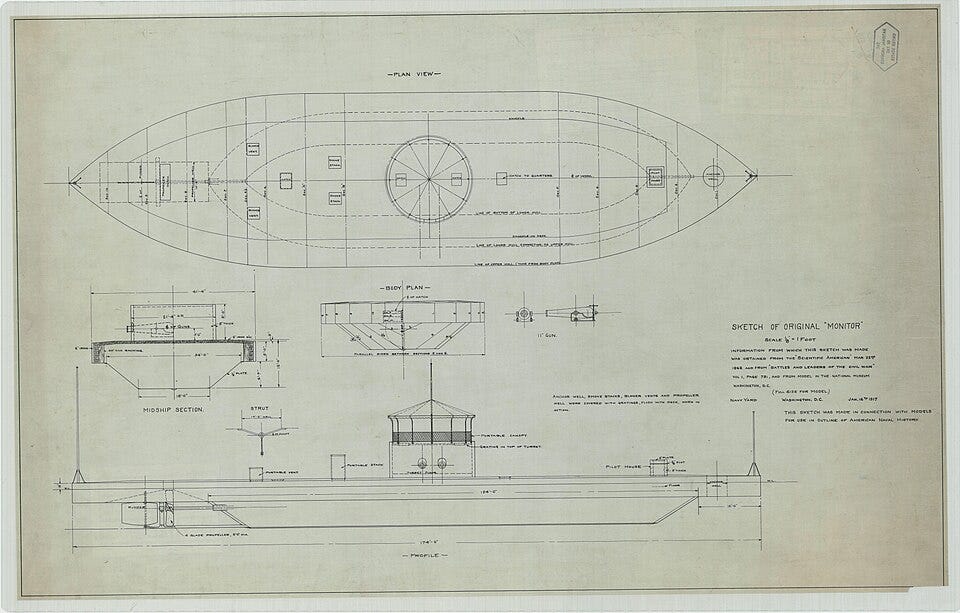

On March 9, when the Virginia returned to finish the Minnesota, a strange vessel appeared. One observer called it a “cheesebox on a raft.” The USS Monitor, the Union’s ironclad, had arrived less than twelve hours earlier. For hours the two ironclads hammered one another at point-blank range, each ship’s shots bouncing harmlessly off its adversary. Both ships withdrew—the Monitor temporarily when her captain was wounded, the Virginia permanently when her commander saw the falling tide and assessed his damage.

A tactical draw, the battle of the ironclads at Hampton Roads was a watershed in naval warfare. Within weeks, the U.S. Navy ordered more ironclads. Britain halted construction of wooden warships. The age of sail and timber had ended in a morning. The age of steel and steam had dawned.

What made the events of March 9 more extraordinary was that the Union’s savior, the Monitor, had been built in only 100 days through a process unrecognizable to today’s defense technologists. This is the story of how it happened, and what it teaches about innovation under existential threat.

100 Days to Revolution

The process started on August 3, 1861, when Congress directed Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to appoint a board to study ironclads and appropriated $1.5 million (about $52 million in 2025 dollars) for construction. Five days later, Welles had his board: three senior naval officers chosen to avoid what he called “humbugs.” That same day, the board advertised in newspapers across six cities for “iron-clad steam vessels of war.” The solicitation gave contractors twenty-five days to submit proposals.

Congress’s appropriation could fund multiple approaches. After several weeks of deliberation, on September 16 the board recommended three distinct designs to field as prototypes in a competitive trial. The Navy wouldn’t commit to production until it saw results. When Congress appropriated $10 million (approximately $350 million in today’s dollars) for 20 more ironclads, the Navy insisted on waiting for operational experience first. On September 21, the board notified the three winners. Two weeks later, contracts were signed.

One contract would change everything. Less than one-thousand words, it demanded delivery in 100 days, set a fixed price of $275,000 (roughly $9 million in today’s dollars) with no cost overruns, and included a performance warranty: if the vessel failed in battle, contractors would repay the government. That vessel would become the Monitor.

Behind it was an unlikely partnership: a disgraced inventor who refused to work with the government, a young venture capitalist who knew how to game the system, and a Navy secretary willing to bet everything on as-yet-unproven technology.

The Heretic and His Necessary Partners

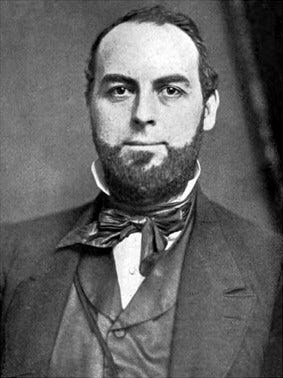

John Ericsson was exactly the visionary the Union needed in 1861—and exactly the kind who would never work with the U.S. government again. The Swedish-born engineer had designed the U.S. Navy’s first screw propeller for the USS Princeton in 1844, but the disastrous results of that venture had left him bitter. During a demonstration on the Potomac, one of the Princeton’s guns exploded, killing Secretary of State Abel Upshur and Navy Secretary Thomas Gilmer. Though Ericsson wasn’t at fault, the Princeton’s commander, Captain Robert Stockton, made Ericsson the scapegoat, going so far as to lobby Congress not to pay the inventor for his contributions to the Princeton. When the Navy’s ironclad solicitation came in 1861, Ericsson had the answer, but refused to submit it.

Enter Cornelius Bushnell, a New Haven financier barely out of his twenties but already one of Connecticut’s richest men. Bushnell wasn’t seeking Ericsson. He wanted technical validation for his own ironclad proposal, and a colleague connected him with Ericsson. At the end of their meeting in Ericsson’s workshop, the inventor pulled out “a dusty cardboard box” and explained his own radical design: a vessel with a submerged hull and rotating turret, “absolutely impervious to the heaviest shot and shell.” The “quick, canny, enthusiastic” Bushnell immediately saw the superiority of Ericsson’s design. Bushnell urged Ericsson to present it to Washington. When Ericsson refused, Bushnell told him he’d do it himself.

This was Bushnell’s genius: recognizing breakthrough innovation and knowing how to deliver it. Bushnell had survived Connecticut’s railroad wars and understood legislatures. He knew where deals got made in Washington: places like the Willard Hotel, where he lobbied Welles “amid the cigar smoke and genial pandemonium.” When the Ironclad Board hesitated, Bushnell lobbied, maneuvered, and persisted.

But even Bushnell’s capital, connections, and tenacity weren’t enough. The innovation needed an internal champion willing to stake everything on it.

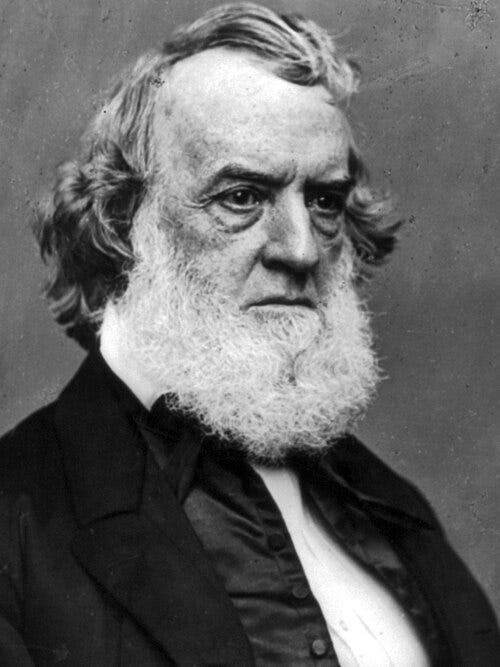

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles was that man. The civilian in charge of a navy dominated by tradition-bound officers, Welles made what one historian calls “the most important technical decision of the war” while “completely unfortified by technical knowledge.” When the Ironclad Board balked, Welles told them he would “assume the risk and responsibility.” If the Monitor failed, Welles risked his position, his reputation, and potentially the Union itself. Welles had already shown his appetite for risk by buying civilian steamers indiscriminately to blockade Southern ports in what critics called the “Soapbox Navy.” Now he was betting on completely unproven technology from a disgraced inventor.

The success of the Monitor required all three men. Ericsson, the heretic, provided the breakthrough. Bushnell, the enabler, furnished the resources and savvy to hack the system. Welles, the bureaucrat, absorbed the risk and shielded the project from institutional resistance. Remove any member of this triumvirate and Ericsson’s ironclad design stays in its box—leaving the Virginia to destroy the Union fleet, ransom coastal cities, and perhaps bombard Washington itself.

Ready for the Next Crisis

It’s tempting to dismiss the Monitor‘s story as a product of existential crisis—possible only when the Union faced annihilation and normal constraints dissolved. There’s truth to that. Risk appetite increases when survival is at stake, and we shouldn’t expect peacetime acquisition to move at wartime speed.

But the Monitor’s lessons aren’t just about speed under pressure. They’re about the fundamental structure of how breakthrough innovation reaches the field.

First, recognize that heretics alone don’t deliver innovation. Ericsson’s genius would have stayed in a dusty box without Bushnell to champion it and Welles to bet his career on it. Today’s defense innovation needs all three: heretics, system-savvy enablers, and risk-absorbing bureaucrats. Build these teams deliberately.

Second, design acquisitions that prioritize outcomes over process. The Monitor‘s contract gave Ericsson 100 days with a performance warranty. The solicitation’s twenty-five-day deadline forced rapid decisions. Modern programs are more complex, but the principle holds: ruthlessly eliminate requirements that don’t serve the mission. Test multiple prototypes competitively. Make contractors share the risk.

Finally, remember the Monitor wasn’t built from scratch: it leveraged existing industrial capacity and proven technologies in a novel configuration. Radical innovation doesn’t require inventing everything anew.

We can’t manufacture existential crisis to drive urgency. But we can build the partnerships, structures, and industrial base now so that when crisis comes we are ready to move with the tenacity of the unlikely partnership that produced the Monitor.

Further Reading

Ferreiro, Larrie D. “The Wrong Ship at the Right Time: The Technology of USS Monitor and Its Impact on Naval Warfare.” International Journal of Naval History, 2015.

Mayer-Sommer, Alan P. “An Historical Case Study of Planning and Control Under Uncertainty: The Weapons Acquisition Process for the U.S. Ironclad Monitor.” Management History 7, no. 2 (2014).

Remling, Jeff. Patterns of Procurement and Politics: Building Ships in the Civil War. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2021.

Snow, Richard. Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimack, and the Civil War Sea Battle That Changed History. New York: Scribner, 2016.