America’s Defense Dollars Are Up for Grabs. Is Your City Ready?

Since the launch of the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) in 2015, the Pentagon has moved to expand the defense industrial base, acquire commercially available technologies, and demystify the national security community for new audiences. The Pentagon is doing its part to reach into emerging regional tech markets.

It’s time for regional economic development organizations to start doing their jobs, too, and respond to the U.S. military’s push to acquire technologies from new suppliers.

By one estimate, we have more than 11,000 nonprofit economic development organizations in the United States employing nearly 170,000 people. Yet at a time that calls for historic economic mobilization to help our military maintain American technological leadership, it’s hard not to conclude that many of these organizations are more focused on hiring legions of consultants to write strategy documents and hosting networking parties for upwardly mobile twenty-somethings.

This is a tremendous missed opportunity given the scale of federal funding in national security. The military and Intelligence Community are the largest funders of R&D in the country. The connections they make are powerful.

Consider U.S. Army-sponsored Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs) with private-sector partners and research laboratories, one of several R&D engagement tools available to the Pentagon. TechLink, a long-standing R&D partner for the Pentagon based at Montana State University, released a report in September on the downstream economic output of such agreements. Evaluating 4,816 CRADAs with 2,799 partners, TechLink noted that over 20 years, CRADAs supported nearly $4 billion in follow-on R&D activity and attracted more than $700 million in outside capital, leading to $1.7 billion in sales to the military and another $9.9 billion in commercial sales.

With that kind of money on the table, why on earth would local economic development organizations not move heaven and earth to participate in the national security industry?

I will single out Chicago, the city I know best, to illustrate the point. I am building an organization, the Frontier Mission Network, to serve the cause of U.S. military modernization and Chicago’s regional tech-based economic growth. To a U.S. Army veteran like me, the essential role of the military in tech-based economic development is obvious. To Chicago’s insiders, I’ve found, it is not. I’ve made countless entreaties to involve Chicago’s economic development organizations in our efforts, with no response but doors slammed in my face.

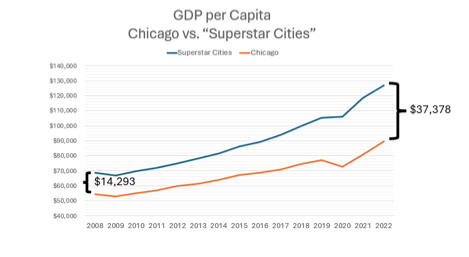

While money and talent pour into the defense sector, cities like Chicago risk falling further behind. Since I moved to Chicago in 2007, the superstar cities—San Francisco, New York, Boston, Austin, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.—have only widened their lead over a city that was once the economic engine of America’s agricultural and manufacturing economy.

Like every major American city, Chicago has built innovation districts, coworking spaces, and business incubators to grow its technology economy. Yet in the past 15 years, we have seen little evidence of meaningful downstream economic production resulting from these efforts. I am confident Chicago is not alone in falling behind the superstar cities.

To understand why, it’s important to distinguish between upstream economic development institutions and downstream economic production—and to align the activities of the former to spark the latter. The existence of upstream institutions does not lead to downstream economic success, in and of itself. “[S]tartup folklore inspires us,” economist Paul O’Brien has written, “but folklore has been bastardized into the belief that if you just build a nice space, innovation will show up like DoorDash.” It won’t.

This is why it is so critical that economic development organizations move away from performative activities that have proven, with several decades of evidence, to yield very little in real economic outcomes. Instead, regional economic development organizations need to be accountable for delivering real, value-adding events: research ideas funded, patents granted, technology licensed, startups seeded (including through federal grants), follow-on private capital invested, and saleable products delivered to a customer.

The Pentagon has long been, and will remain, a customer with extraordinary resources to power the lab-to-market pipeline from start to finish. Silicon Valley understood this from the beginning. Since just after World War II, Stanford Research Park has linked principal investigators and new ventures to the military across a range of technological fields. Similar if nascent efforts are emerging elsewhere, including the Defense Alliance in Minnesota and the Pacific Northwest Mission Acceleration Center in Seattle.

Both for the cause of military modernization and for regional growth, economic development organizations need to drive activity from the lab to military and commercial users. Here’s how:

Connect Stakeholders

For researchers at the 15 universities with a DoD-sponsored University Affiliated Research Center (UARC), the connection to the Pentagon was established long ago. For everyone else, universities and national laboratories need to be more proactive in engaging program officers leading the Pentagon’s 14 critical technology areas and responding to solicitations posted by the National Security Innovation Network, among other sources.

Economic development organizations need to establish a robust line of communication between stakeholders and the military. Sometimes that’s just a matter of getting some face time with Pentagon program officers, understanding their needs and brokering relationships with local researchers. I’ve found even senior program officers are surprisingly responsive to cold emails.

Support for research institutions should continue through technology transfers. Economic development organizations should be supporting startups to produce technology licensing proposals that offer laboratories a realistic plan to commercialize their work. Laboratories cannot be expected to invest time and resources in licensing technologies to startups that lack a feasible path to profitability.

Bridge the Valley of Death

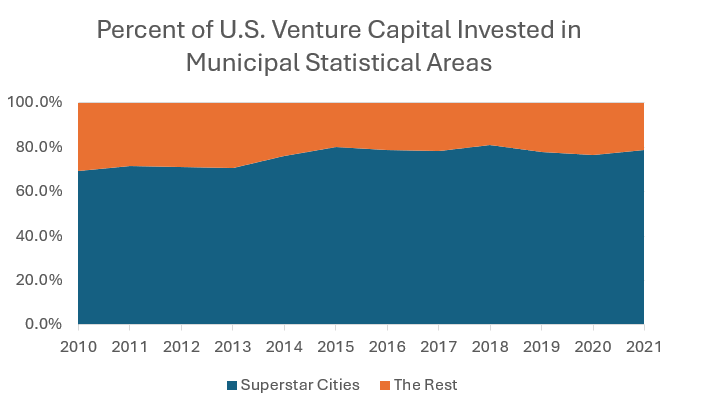

There have been several well-intentioned efforts, including one co-founded by our now-vice president, to expand venture capital investment outside of the superstar cities. But such efforts are the exception, and they haven’t managed to close the gap between struggling and prosperous regions. The rest aren’t rising. Matter of fact, Pitchbook data suggest “the rest” are in fact . . . falling.

Are venture capital firms ignoring opportunities outside the Bay Area and other superstar cities, or are they simply following value creation? A 2010 paper by Harvard Business School’s Josh Lerner, analyzing over 1,000 firms, points to the latter.

“(V)enture capital offices are concentrated in locales where previous investments by venture capital firms were successful,” Lerner wrote, adding that “moving from the 25th percentile of the regional success rate for venture capital investments over the past five years to the 75th percentile of the regional success rate increases the number of offices in a (Combined Statistical Area) by a factor 2.3.”

What this suggests is that non-superstar cities can’t bank on VC to swoop in and save the day. They need to get their houses in order and search for alternate sources of funding to build the kinds of innovation ecosystems that can attract VC.

The good news is, there are many new grant programs and spending authorities to bridge funding gaps that limited private VC markets won’t. These include:

Middle Tier of Acquisition (MTA) authorization, enabling DoD acquisition officials to work with suppliers of technologies considered ready for deployment within five years, using a more streamlined acquisitions process.

The Air Force’s Strategic Funding Increase (STRATFI) program, launched in 2020, to provide an additional layer of funding after the two-phase Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, providing as much as $15 million in additional support to complete development of a technology.

The Office of Strategic Capital (OSC), providing the Pentagon with something like a bank, issuing loans and loan guarantees to firms operating in critical technology areas.

Instead of putting startups before venture capitalists who are unlikely to support high-risk R&D and product development outside of the superstar cities they know, economic development organizations need to support a model that instead looks toward federal and defense programs that are specifically designed to bridge funding gaps after a concept has been proven and a prototype produced.

Chart Dual Uses of Patented Technologies

“The US has more Nobel Prizes for science than the UK, Germany, France, Japan, Austria, and Canada combined,” journalists Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein write in their recent book, Abundance. “But if there were a Nobel Prize for domestic deployment of technology – even technology that we invented – our legacy wouldn’t be so sterling.”

The U.S. military has historically addressed this gap, operating at the intersection of research, development, and demand, and acting as an indispensable partner in realizing the economic value of science. Economic development organizations, as foot soldiers in the “real economy,” should similarly explore ways to translate patented technologies into marketable products for both commercial and defense sectors.

Local institutions can often be helpful in supporting dual-use go-to-market pathways for local startups. For example, a sensor designed for the healthcare sector to monitor brain activity might also track fatigue in police officers and fighter pilots. We have, in fact, brokered conversations between a Chicago startup and relevant Pentagon program officers, while also working to engage the Chicago Police Department, to explore dual-use applications of their technology.

Prize contests can provide a blunter tool in commercializing technologies. As little as $10,000 has been shown to attract participants. DARPA prize contests in the mid-2000s famously sparked development of technologies that would accelerate autonomous vehicles. In a recent New York Times op-ed, former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and coauthor Selina Xu highlighted how Chinese farming villages are hosting similar competitions to apply AI tools to improve harvest yields. Why shouldn’t economic development organizations sponsor similar initiatives to translate new discoveries into real-world applications—especially within a defense context?

Accountability for Economic Development Organizations

I believe it is a moral imperative of innovation communities to support American national security. But even if you are unmoved by appeals to American strength, consider this: how could any region ignore a single entity with a trillion-dollar annual budget as a potential driver of local economic growth?

That’s a question that not only needs to be asked of economic development organizations, but those who fund them. If organizations charged with growing regional economies continue to ignore the world’s largest funder of R&D, is their true purpose economic development or just safeguarding their own safe, six-figure salaries?

We need the full breadth of the American innovation economy focused on national security problem sets. At present, economic development organizations are MIA. If corporate funders want to actually grow their regions and support American technological leadership, there’s a small but growing crop of defense-focused (or at least defense-literate) economic development organizations ready to put dollars to better use.

Thomas Day is the executive director of Frontier Mission Network, a business consortium dedicated to serving the Chicago region’s national security and defense technology sector. He is also a lecturer in tech-based economic development at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago.