The CDC America Needs

Built for war, the CDC has forgotten how to fight.

Matthew McKnight is a Belfer Center fellow at Harvard Kennedy School, a former Marine Corps officer, and the head of biosecurity at Ginkgo Bioworks.

The ongoing restructuring of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is long overdue. The institution requires a fundamental reboot of purpose—returning to its core mission as America’s frontline defense against infectious disease and biological threats.

America’s public-health agency was originally built for war, but it has forgotten how to fight. The hard truth is simple: the CDC wasn’t ready for COVID-19, and it is even less prepared now. The agency that was supposed to protect us from biological threats was unable to even produce a working diagnostic test for the biggest pandemic in a century. That foundational failure, among other structural flaws identified by CDC itself, severely crippled our response.

In the era of AI-engineered pathogens, non-compliance with the Bioweapons Convention, and threats of biowarfare from our adversaries, the CDC must become the operational frontline engine for defending the nation against biological threats.

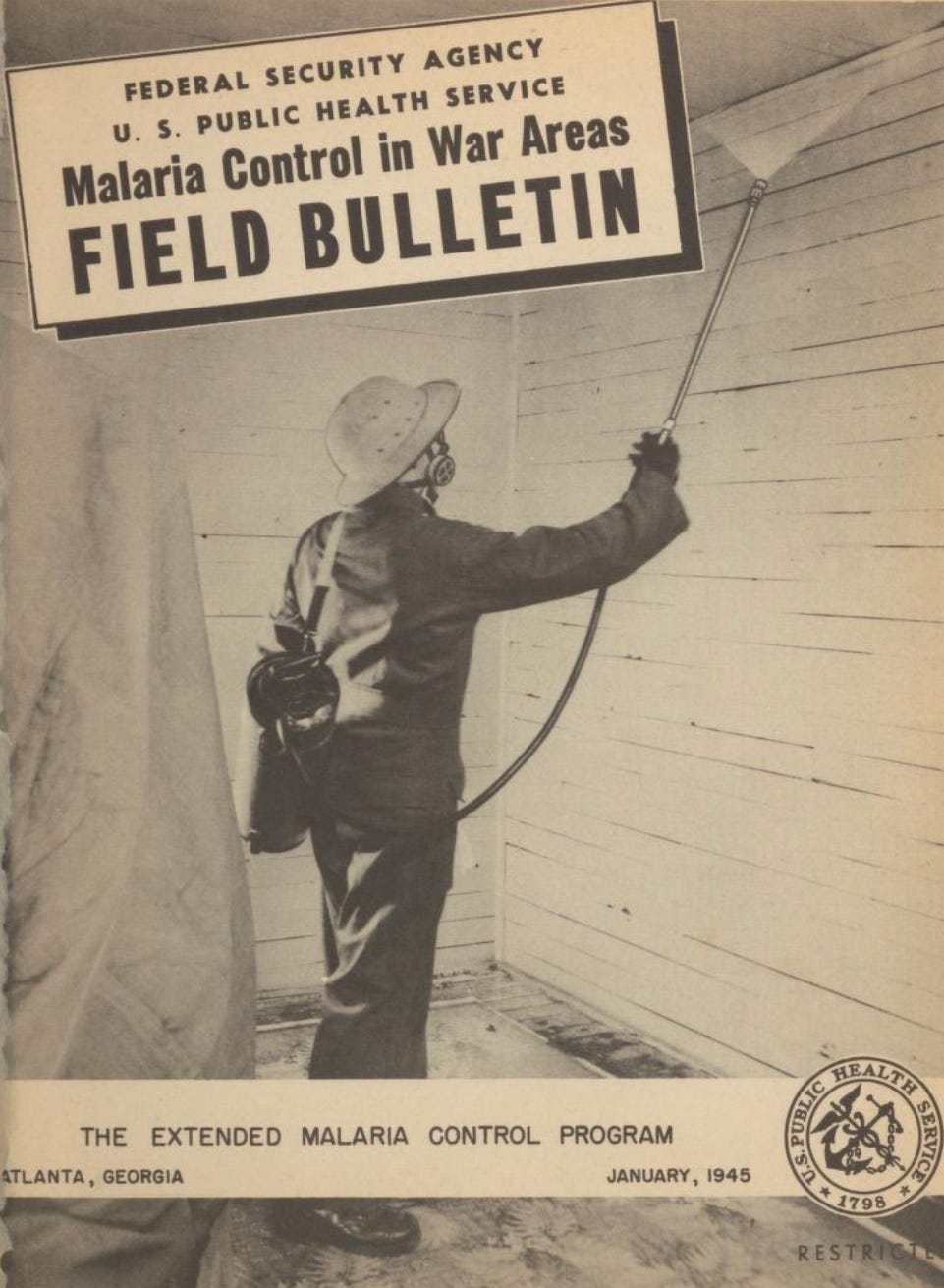

That means going back to its roots. The CDC was born out of conflict. Its forerunner, the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas, was an effort during the Second World War to fight malaria on military bases. When the agency was formerly established in 1946 as the Communicable Disease Center, it retained its wartime bias toward action, working to wipe out malaria from the American South. Its early leaders were field operators armed with trucks, insecticide, and data—not bureaucrats debating word choice. The CDC’s success in eradicating malaria cemented its role as the nation’s front line against infectious disease, a mission defined by speed, logistical, and operational excellence. It was built as an on-the-ground disease-fighting force, but over time, layers of excessive caution have diluted the core mission, effectively leaving CDC as an advisory and financing body.

This mission drift has unfolded over decades. CDC’s effective contribution to the HIV crisis in the 1980s and the success of vaccines led to the false perception that infectious disease was a solved problem. The subsequent decades of “peacetime” in the war against pathogens pulled the organization into complacency and cumbersome processes filled the vacuum. Resources were directed toward non-communicable disease and inwards toward policy guidance, messaging, and academic research instead of building the operational muscle needed to fight the next outbreak.

By the time COVID hit, the CDC was more of an ossified bureaucracy than a command center. When I led large-scale detection programs across 26 states for Ginkgo Bioworks in support of the CDC during the pandemic, I saw firsthand how the CDC’s systems slowed action when speed mattered most. The people were dedicated, but the structure was paralyzed by process. When the agency did effective work, it was because it returned to its roots, playing a key role in operational activity. During Operation Warp Speed, for instance, CDC supported vaccine distribution and monitoring, as well as testing systems for delivery.

The CDC needs to learn from this history, because the world we face today looks increasingly like the days of CDC’s inception. Modern biological threats demand wartime preparation. At the recent United Nations General Assembly, President Trump rightly drew attention to the danger posed by biological weapons—danger that cannot be met with archaic and ineffective systems that failed their most recent test.

Some have declared “the death of public health” in the wake of recent CDC layoffs. Their argument is based on a conclusion that the system was working or that it could be fixed from within. It wasn’t and it can’t be—and if a global pandemic wasn’t enough to spur major change, something more extreme is required.

The next era demands a fundamentally different approach: relentless focus on scalable technology, real-time global detection, integrated surveillance networks, and data infrastructure to respond to outbreaks before they become catastrophic. When the next pandemic or deliberate biological attack inevitably hits, we will have hours to respond, not months.

During the pandemic, companies delivered large-scale testing because wartime opened pathways outside of bureaucratic channels. Technology was deployed and information flowed to the local level—directly to business owners and principals, teachers, and parents at schools, bypassing layers of remote health authorities. Trusted local leaders could make community decisions, based on real data, in real time. That’s what transformative technology deployment should accomplish. Until we rebuild the CDC in this image, America will remain untrusting and dangerously unequipped.

We need a CDC that embraces, not resists, cutting-edge approaches. One that acts as an experimental platform, not a bottleneck. A CDC that treats biosecurity the way we treat cybersecurity: as a national-scale mission powered by public-private partnership.

The CDC must serve as a critical component of America’s overall biological defense capabilities—as a tool of hard power. We don’t put American military bases around the world as a gesture of goodwill. We do it to project strength and deter threats before they reach us. The CDC should operate with that same logic and culture. It should be forward deployed, globally networked, and technologically dominant.

As Health and Human Services Secretary Robert Kennedy, Jr. wrote in the Wall Street Journal, we need upgraded capabilities to provide and deliver a unique infectious disease detection and response asset for America and its allies. Every dollar should be put toward strengthening technical and operational capacity: sequencing, global data integration, and real-time pathogen detection to create a global Biothreat Radar platform for America and its allies. The CDC can lead in generating an active biointelligence (BIOINT) layer, a function the World Health Organization has failed to provide, to identify and coordinate response to outbreaks anywhere in the world.

The CDC today does far more than outbreak response. Its work on chronic disease, environmental health, and issues like lead poisoning has saved countless lives. Those missions remain important public health goals, but they belong in institutions designed for them. Organizations perform best when their purpose is sharp. The CDC should work relentlessly to stop infectious disease, while its other public-health functions could be spun into agencies better suited for long-term health and prevention.

The CDC has many talented and dedicated people dedicated to our country, but pretending the organization doesn’t require radical reform is the most dangerous choice we could make. The worst outcome isn’t overreaction. It’s inertia. Carrying out this mission reset requires the CDC to rebuild its culture and bring in a new generation of scientists, technologists, and operators who embrace this call to action. The ongoing restructuring is a rare chance to make that cultural reset real.

Change is hard, but the system must evolve. The next biological threat, natural or man-made, will test our ability to act, not deliberate.

If America can build radar to track missiles and satellites to spot nuclear launches, it can build the infrastructure to detect and defeat biological events. The CDC should be core to that system—the front line of America’s defense in the biological century.

That’s the CDC America needs.