Joseph Desch, American Codebreaker

A quiet engineer in Ohio united government and industry to break the Nazi Enigma.

Peter Minetos is a communications strategist at Palantir and former press secretary on Capitol Hill.

In 1942, as war raged across the globe, one of the most consequential alliances in the history of technology was forged—not on a battlefield, but in the heart of Ohio. While the world’s attention was fixed on the front lines, a quiet engineer named Joseph Raymond Desch stood at the center of a revolutionary partnership between the U.S. Navy and a private American company, working behind the scenes to tip the balance of the war.

That company was National Cash Register (NCR), a Dayton firm best known at the time for making business equipment like mechanical registers and punch-card machines. But behind the factory floor, NCR was also home to a small, powerful team of electrical engineers and inventors—including Desch—who had been experimenting with cutting-edge electronics well before the war. When the Navy came looking for a way to industrialize codebreaking, they found their answer in Dayton.

Working together, NCR and the Navy established the United States Naval Computing Machine Laboratory on NCR’s corporate campus. This unique partnership brought together Navy officers, civilian engineers, and NCR’s manufacturing expertise under one roof.

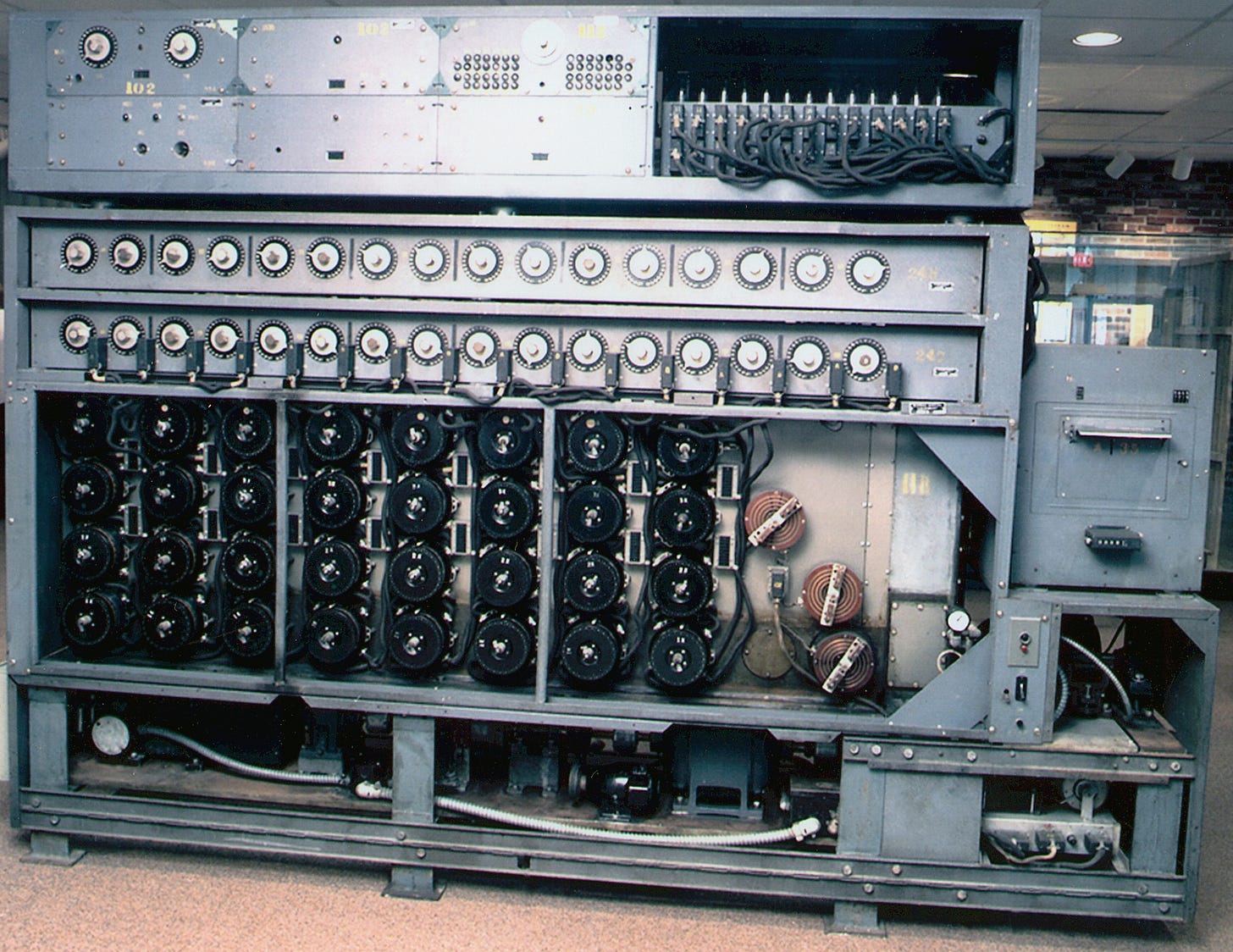

At this laboratory, where the Navy’s most advanced cryptographic machine work took place, American civilian Joseph Desch helped design and deliver 121 versions of a high-speed, electromechanical device called the Bombe, which played a crucial role in unlocking the secrets of the Nazi Enigma during World War II.

The Enigma Challenge

The German military’s use of the Enigma machine created a seemingly unbreakable wall of encryption. The Enigma used a series of rotating wheels, or rotors, that shifted position with every keystroke, scrambling each letter. Every day, the Germans would set the rotors and plugs to new starting positions, creating millions of possible configurations; without knowing the exact settings, the code was incredibly difficult to break. Enigma was how the Nazis coordinated everything from battlefield orders to U-boat attacks in the Atlantic. Cracking its code wasn’t merely an intellectual puzzle, it was a matter of life and death: Allied supply ships were being sunk at an alarming rate. Without the ability to anticipate and outmaneuver Germany’s fleet, the war could tilt further in the enemy’s favor.

British mathematicians led by Alan Turing had already made significant progress toward cracking Enigma at Bletchley Park, developing an early version of the Bombe to decrypt German army and air force messages. But the U.S. Navy faced a more difficult variant: the four-rotor Enigma used by German submarines. Cracking this code required more computing power, more speed, and a new design.

That’s where Desch came in.

From Dayton to Discovery: Desch’s Early Years

Joseph Desch was born in Dayton, Ohio. His father—a craftsman and farmer—encouraged his son to learn how to use the right tools to solve his problems, fostering a spirit of curiosity and hands-on experimentation from an early age. By age 11, Desch was a radio enthusiast, sparking a lifelong fascination with electronics and communication. As a teenager, he built his own laboratory, experimenting with vacuum tubes to pass signals and impulses, early steps on a path that would later revolutionize codebreaking.

In 1926, Desch passed his amateur radio license exam and began working at the University of Dayton repairing radios, laying the technical foundation for his later achievements. He eventually found work at the processing laboratory division at General Motors, and in 1938 followed a mentor to NCR, joining the electrical research laboratory under the guidance of the company’s president, Colonel Edward Deeds.

By the early 1940s, Desch had already designed one of the earliest high-speed electronic counting circuits, using vacuum tubes to reach performance levels far beyond anything in commercial use. He had even invented a binary computer for banks to use as an electronic calculator—an early glimpse of the digital revolution to come.

Building the American Bombe

In March 1942, the U.S. Navy contracted NCR to build Bombes—machines designed to process the German Navy’s complex four-rotor Enigma messages. Joseph Desch, head of NCR’s electrical research laboratory, was appointed as the principal engineer for the project. The British had already done invaluable work, and succeeded in breaking the four-rotor Enigma in December 1942. The Americans picked up the torch and pressed on, aiming to develop a faster and more reliable machine by fundamentally redesigning it to handle the increased cryptographic complexity.

The heart of this redesign was Desch’s push to incorporate vacuum tubes—a new idea at the time. Vacuum tubes were small, sealed glass cylinders that could control electric signals by allowing or blocking the flow of electrons. They acted as fast, reliable electrical switches or amplifiers. Unlike electromechanical relays, which worked by physically flipping switches on and off (slowing operations and causing wear), vacuum tubes used electric fields to allow or block the flow of electrons almost instantaneously. This meant they could switch on and off thousands of times per second. By using vacuum tubes, Desch’s design could perform logical calculations at unprecedented speed and reliability, making it possible to test millions of possible Enigma settings each day. This leap in processing power was crucial for codebreaking, as the German Navy changed their Enigma settings daily. Only a machine fast enough to keep pace could give the Allies the information they needed in time.

Many in the military and engineering communities were still skeptical of vacuum tubes. They were considered unstable and fragile for sustained, high-speed operation. Desch disagreed. Drawing on years of experience building high-speed counters and signal processors, he advocated for integrating vacuum tube logic to dramatically speed up the decryption process. His insistence on this direction required pushing back against conventional wisdom and military preferences for more familiar electromechanical systems. Desch had to make his case against institutional skepticism and operational conservatism. He understood that wartime innovation couldn’t wait for red tape.

Desch’s vision was to create a hybrid machine, combining mechanical rotors that would physically simulate the changing positions of the Enigma’s rotors with electronic logic circuits that could instantly detect contradictions in the wiring. These electronic logic units used vacuum tube comparators, which are components that evaluate electrical conditions. In this case, they would look for situations where a given Enigma configuration couldn’t possibly produce the decrypted result—allowing the Bombe to quickly discard bad settings and move on.

It was a clever and efficient system: the rotors turned rapidly through different key combinations, and the vacuum tubes instantly “judged” each configuration. The combination of mechanical motion and electronic logic allowed Desch’s Bombes to process hundreds of thousands of potential keys per second—something no purely mechanical device could match at the time.

The Power of a Mobilized Workforce

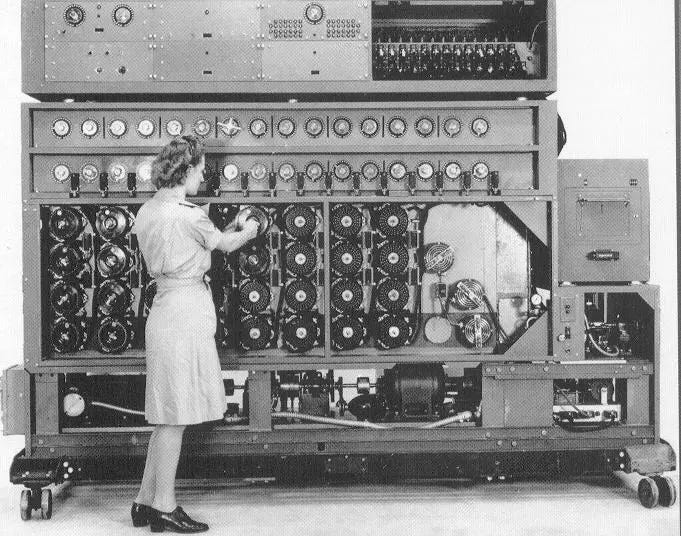

But machines alone weren’t enough. To operate the Bombes around the clock, the Navy deployed an extraordinary team of over 600 women from the WAVES—Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service—who were trained to configure, monitor, and maintain the machines. The women worked on certain parts to assemble the code-breaking machines for the military. Strict secrecy was enforced: they were not allowed to communicate with other civilians about their jobs, or even to talk about them among themselves outside of work. Many had no idea the full importance of their contribution to the war effort.

The Bombes, run by the WAVES, were connected to the broader Allied intelligence pipeline. Once a plausible Enigma setting was found by a Bombe, cryptanalysts in Washington would use it to decrypt intercepted German messages. These decrypts, known as Ultra intelligence, directly informed naval operations: rerouting convoys away from ambushes, revealing submarine locations, and accelerating the overall Allied campaign in the Atlantic. Through it all, Desch remained in Dayton, overseeing production and innovation in the shadows.

The Bombe’s Impact

In May 1943, Joseph Desch’s American Bombes, built at NCR’s Dayton facility, began arriving in Washington, D.C., transforming the Allied effort in the Battle of the Atlantic. These high-speed machines, enhanced by Desch’s pioneering use of vacuum tubes, tested millions of Enigma rotor combinations in a short time, such as a 20-minute run, enabling the rapid decryption of the German Navy’s complex four-rotor codes. The end result: Ultra intelligence powered by the Bombes enabled the Allies to reroute convoys, hunt U-boats, and disrupt German operations, saving countless lives and shortening the war. Approximately 121 Bombes were produced, showcasing American ingenuity and industrial prowess under wartime pressure.

More Than a Hero

Joseph Desch never sought the spotlight. He rarely spoke publicly about his work, even decades later, when the Bombe program was finally declassified. In part, this reticence stemmed from the enormous psychological toll the work had taken on him during the war. The burden of knowing that his codebreaking efforts could lead directly to the deaths of thousands weighed heavily on his conscience, underscoring the profound personal sacrifice he made in service to his country. His daughter, Deborah Desch Anderson, grew up knowing little about her father’s wartime work; it was only after his death that she began to uncover the vital role he played in Allied codebreaking efforts. Desch retired from NCR in January 1972. He died on August 3, 1987, taking many of his secrets to the grave.

But Desch’s legacy is profound. He built machines that changed the direction of war. He trained a workforce and laid the technical groundwork for the intelligent systems we rely on today.

Fast forward to 2025, and it’s clear the world needs more private-sector patriots. The world is now in the midst of a new kind of arms race. Artificial intelligence has become the decisive terrain for national security, global influence, and technological dominance. And once again, the United States is turning to its private sector for technical tools and leadership.

Joseph Desch provides a model of successful public-private partnership. When America’s government partners with its builders, scientists, and engineers in shared purpose, it can overcome the most daunting challenges.

Joseph Desch and the NCR proved that once. We can prove it again.