Eugene Fubini, Heretic in the Control Room

He jammed Axis radars, then built the bridge between industry and government in the Cold War.

Ross Fubini is the founder and managing partner of XYZ Venture Capital, an early-stage venture capital firm. He is the grandson of Eugene Fubini.

A Note From the Author: As our protagonist’s grandson, I’m cognizant that regression to the mean tends to dilute both impact and insight. But I love that I get to carry an echo of his legacy into our work at XYZ Venture Capital, backing founders building systems that move his mission forward.

It’s July 1943, and Allied forces are gearing up for the invasion of Sicily — Operation Husky. Bombers preparing to strike Axis targets across North Africa and Southern Europe stare down the barrel of a growing threat: radar.

German detection systems have been evolving fast, locking onto aircraft with brutal precision. Allied pilots know it. Commanders know it. Success depends on slipping past the enemy’s gaze. And then — just as the Allied planes approach their targets — the Germans’ radars blink out. Silence. Darkness. Confusion.

This wasn’t luck. It was physics.

At the heart of this engineered blackout was Eugene Fubini — a 5’1” Italian physicist with a volcanic mind and the bearing of a quiet revolutionary. A Jewish immigrant who’d fled Mussolini’s regime, he’d helped invent and deploy radar jamming systems that blinded German operators and bought Allied aircrews a precious edge.

Radar jamming wasn’t just a tactical innovation. It was a new kind of weapon. And it marked the beginning of Eugene’s career quietly reshaping how America builds and maintains its military edge. His approach didn’t call for more weapons. It emphasized better systems, faster iteration, and smarter procurement.

Perhaps most importantly, Eugene’s life and career demonstrated a high tolerance for heresy in service of long-term advantage.

A Mind Molded in Exile

Born in 1913 in Turin, Eugene grew up in the shadow of brilliance. His father, Guido Fubini, was a mathematical giant — his eponymous theorem is still taught to calculus students today. Learning was an imperative, and excellence wasn’t optional. Eugene delivered. He earned doctorates in both physics and electrical engineering, and held a faculty post at the University of Turin while still in his twenties.

Then, like for so many, fascism came for him. Mussolini enacted the Italian Racial Laws in 1938, stripping Jews of their citizenship and expelling them from academic and professional life. The Fubinis were abruptly forced into exile.

A sympathetic uncle smuggled them through Switzerland, France, and finally to the U.S. Eugene, now “Gene” to his friends, took no time to catch his breath. With the quiet help of his father’s friend, Albert Einstein, he landed first a post at Princeton and then a full-time technician job at the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS).

The role couldn’t have been more apt in a country girding for war. It wasn’t glamorous, but it gave Gene room to make major contributions to radio and television signal processing. The same physics he brought to bear on ultra-high frequency radio and microwave propagation directly informed his eventual work in radar and electronic countermeasures.

Over the next three years, the building wave of conflict catapulted Gene first to Harvard Radio Research Lab — a hotbed of innovation in radar and jamming theory — and then immediately into the thick of things. By 1943, he was embedded with Allied forces in Northern Africa, designating the systems that would scramble German detection equipment and protect Allied air missions. During the invasions of Italy and Southern France, radar jamming became the difference between mission success and mass casualties.

Gene’s contributions during the war earned him attention and clearance at the highest levels. More importantly, they cemented his strategic worldview: military advantage no longer hinged on brute force. The future of national security would be driven by sensing, computing, decision loops, and systems integration. This had to be his life’s work.

The Insider Who Refused to Go Native

After the war ended, Gene’s purpose led to the commercial world. He joined the Airborne Instruments Laboratory Company, where he continued to innovate in the field of reconnaissance electronics and churned out patents for electro-magnetics and microwave applications. But in the back of his mind, he knew he’d need to get closer to policy to make real change.

He got his chance in 1961, with an invitation to join the Office of Defense Research and Engineering. Once again, his ascent was steep. President John F. Kennedy appointed him Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering just two years into his government career. Suddenly, he was atop the Pentagon research apparatus — at the height of the Cold War.

This wasn’t just a job for Gene. It was a crucible.

Under Robert McNamara, the DoD was shifting toward centralized procurement and outcome-driven R&D. Gene was a perfect fit: precise, stubborn, and utterly unwilling to fund science for science’s sake.

He brought with him the same convictions that had shaped his radar work: that the U.S. could only maintain strategic advantage with technical superiority — and that this would require a wholly different operating rhythm than the one preferred by the Pentagon’s more cautious custodians.

His remit was vast. He oversaw nuclear R&D, space surveillance programs, emerging computing initiatives, satellite comms, and the earliest stages of digital encryption.

At the same time, he forced agencies like the NSA to rigorously justify their programs, cutting bloated, opaque budgets and consolidating theater-level processing centers in Europe. He chaired the Communications Security Board, reviewed classified satellite collection strategies, and routinely challenged senior leaders to articulate not just what they wanted to build — but why it mattered.

Suffice to say, not everyone loved working with him. In his words (and with the dry clarity of someone who stopped seeking approval a long time ago): “I seem to have become a controversial character here.”

But for all his confronting tendencies, Fubini wasn’t a purist. He was a builder. He understood that the systems most worth defending were often the ones most likely to upset entrenched interests.

Building the Bridge: Government x Industry

In 1965 — well into the Lyndon Johnson administration (and Vietnam War) — Gene decided to step out of his Pentagon role and do something few at the time had done: he carried the playbook for strategic R&D into industry, first as a senior executive at IBM and later on the board of Texas Instruments.

In the process, he revolutionized the way the private sector side of defense worked. Solidifying the role of corporate R&D as a national security asset, he advocated for long-term investment in advanced computing, secure communications, and defense-grade interoperability at a time when commercial technology firms were still seen as outsiders to the mission.

At IBM, he helped align product strategy with government priorities, shaping how computing systems would serve the military, intelligence agencies, and NASA. His influence extended to procurement strategy (providing a hyper-critical insider’s view of how the government buys), technical standards, and even internal corporate culture.

He was one of the earliest advocates of industry serving as a co-equal partner in defense innovation — not just a contractor, but a counterpart.

Gene’s model lives on today in the dual-use companies that serve both government and commercial customers, and increasingly define the defense startup landscape. Palantir, Apex Space, Forterra and others are operating along the same axis that he pioneered: moving fast, staying flexible, and building systems that scale across both government and commercial domains.

In all these ways, his impact was less about singular inventions and more about the connective tissue. The loops. The interfaces. The infrastructure that allowed technical advantage to be absorbed and operationalized at scale.

He understood that to move the mission forward, you often had to change the institution — not just the tool.

The Arc Continues

Fast forward to 1996, the Department of Defense created the Fubini Award, given annually to individuals whose contributions to national security research and development have shaped U.S. strategy. Naturally, Gene was the first recipient.

But for him, legacy was never about medals or job titles. It was the transmission of mindset — the ability to operate across disciplines, challenge orthodoxy, and stay fluent in both theory and practicality.

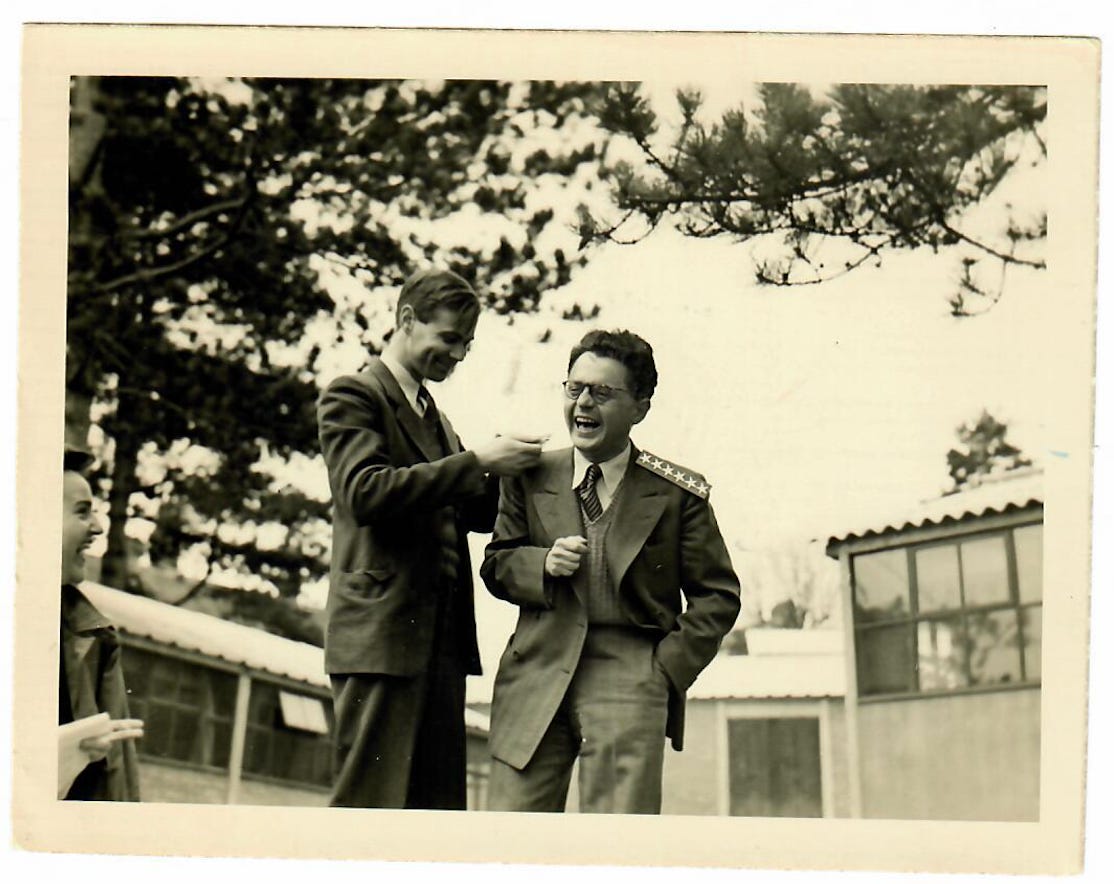

As his grandson, I saw that mindset up close. For five years of my childhood, I lived with my grandparents. I watched people from across the national security and academic worlds come to our house seeking my grandfather’s advice. He was older by then — quiet, still sharp, unassuming. But the steady stream of generals, university presidents, and former cabinet officials told me something that words never could:

The systems we live inside don’t maintain themselves. Someone has to build them. And someone has to keep pushing them forward.

I didn’t fully understand what he had accomplished until much later. It wasn’t until my twenties that I began digging into his papers and learning more from family who saw the many varied sides of him. It was clear just how large a footprint he left — not only on the Defense Department, but on the shape of the technology sector as it serves our defense goals.

That legacy is one of the reasons I’ve spent the last decade investing in leading technology companies — writing first checks to defense startups like Anduril and Apex and backing founders who are dedicated to pushing systems forward. These companies are doing the vital work of building the next layer of infrastructure for U.S. capacity, security, and — perhaps even more to the point — capability to serve our citizens better.

Today, I don’t pretend to be following in my grandfather’s footsteps. But I carry some of his questions. What systems are we building? Who do they serve? And how are we building them to last?

Gene Fubini understood — far earlier than most — that the future would be won not by the biggest bombs or the fastest planes, but by the teams who could integrate sensing, computation, and judgment faster than anyone else.

He built toward that future. That future is here. And now we need more heretics.