ERPs Have Failed Our Military

Traditional software systems are structurally misaligned with modern warfare.

This is a guest post by JJ Wilson, the president and co-founder of Adyton. Previously, JJ was a Special Forces soldier in the U.S. Army, with multiple combat deployments to Afghanistan. His military awards and decorations include the Combat Infantryman Badge, the Bronze Star, the Military Freefall Jumpmaster Badge, and the Special Forces Tab. Prior to Adyton, JJ worked primarily in enterprise technology strategy at The Boston Consulting Group.

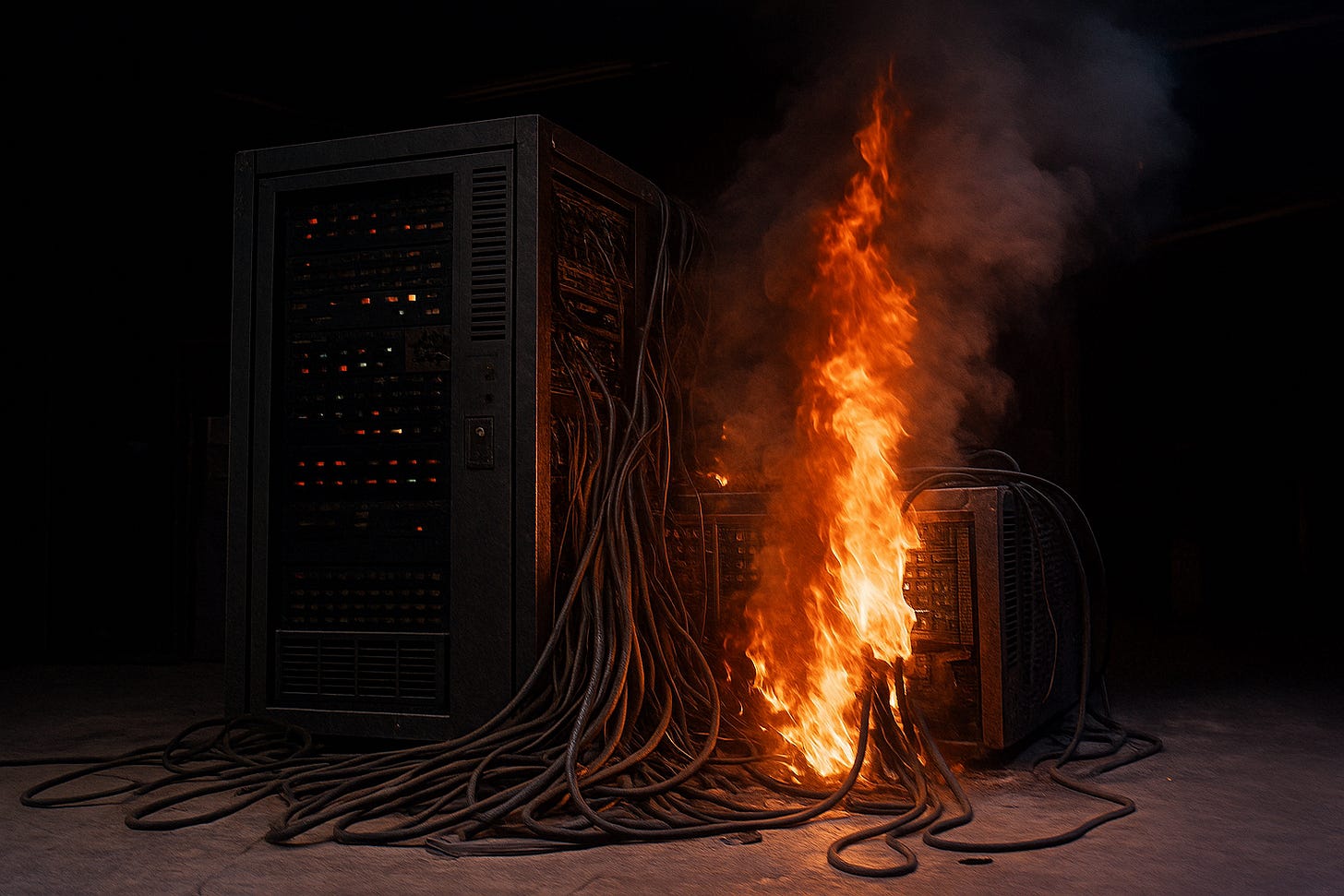

For decades, the Pentagon has invested billions in enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems in pursuit of integration and auditability. The failings are clear: cost overruns, delays, frustrated users, and thirty years of failed audits. The reason for these failings is equally clear: ERP systems are structurally misaligned with the operational realities of twenty-first century warfare.

Total-Spectrum Warfare

During World War II, the United States had a “total war” mindset. General Motors and Chrysler manufactured tanks, guns, ammunition, aircraft engines, and more. IBM made rifles. Ford’s Willow Run plant became synonymous with the Arsenal of Democracy, producing bombers at a prolific rate. In essence, the civilian population and private industry were a part of the warfighting effort.

The United States has lost the concept of total war in the twenty-first century—but our enemies have not. Modern war is total-spectrum conflict: adversaries contest U.S. forces simultaneously across physical, informational, economic, and narrative domains, with technological advances further expanding the scope of the modern battlespace.

Despite these threats, how our military does business is stuck decades in the past, technologically unable to keep pace with the changing nature of war.

ERP systems, which emerged in the 1980s, were at the time the best answer to the question, “How do we unify sprawling business functions into a single integrated system?” Decades ago, large organizations, our military included, had no real alternative. Networks were limited, modular SaaS didn’t exist, and integration across dozens or hundreds of bespoke systems was impossible. ERPs tightly coupled business logic, databases, and user interfaces, which was a rational solution in an era of mainframes and centralized IT.

Technologically, the modern enterprise no longer lives in an era of mainframes and centralized IT—except for our military.

ERP Projects Cannot Succeed in Defense

Encoding hundreds of interdependent processes into a single, tightly coupled system creates a sprawling web of risk factors, any one of which can derail the effort. Data migration bogs down in inconsistencies. Customizations lock programs into brittle code that can’t be upgraded. Organizational change requirements exceed user bandwidth. Governance cycles freeze requirements long before delivery. And leadership turnover severs accountability. The result is that even with ample funding and skilled teams, ERP programs rarely deliver more than partial functionality—and often collapse altogether.

The result is decades of ERP horror stories, from businesses and governments alike. In 2022, an ERP deployment by the City of Birmingham in the United Kingdom ballooned to over 700 percent of the original budget. Zimmer Biomet lost billions in market cap due to ERP-caused disruptions. In 2015, Target wasted $2.5 billion in an attempt to enter the Canadian market, withdrawing completely after severe supply chain collapse caused by a faulty ERP rollout. MillerCoors abandoned a consolidation effort in 2014 after pouring hundreds of millions into defects and delays. The list goes on and on.

If organizations with this level of capital, leadership talent, and IT capacity can’t achieve success, the underlying model itself is suspect: ERP projects offer a 70 percent change of failure—of which 25 percent are catastrophic failures. No serious policymaker would green-light a weapons system with probabilities that bad, yet ERP still remains the default for business systems within our military.

The fundamental problem is that the ERP model itself is structurally misaligned to the military’s environment and cannot succeed. Commercial enterprises can usually consolidate decision rights, manage scope, and enforce accountability across business units. The military cannot. Defense ERP projects are scoped across entire services, often touching every function from pay to supply, and then managed under acquisition rules designed for weapons systems, not software. Oversight is diffuse, incentives are misaligned, leadership turnover is rapid, and governance cycles freeze requirements years before delivery. Programs are staffed by rotating uniformed officers and supported by prime contractors rewarded for scale, not speed.

What is merely extraordinarily difficult in the private sector becomes virtually impossible in the Pentagon.

The proof is in the failed projects and wasted dollars: The Navy spent over $1 billion on four ERP pilots in the 1990s and 2000s, all of which were scrapped. The Air Force’s Expeditionary Combat Support System consumed seven years and $1 billion before being abandoned without delivering a usable product. The Army’s flagship Integrated Personnel and Pay System (IPPS-A), built on PeopleSoft, has been delayed for years and has already cost about $1 billion more than initially expected. The Navy’s NP2 program has stalled and is now expected to be re-scoped or recompeted after years of drift. The Air Force canceled a massive HR system after wasting hundreds of millions.

There’s a reason why, despite billions invested, no military ERP program has ever been delivered on time, on budget, and at scale.

The Strategic Shift: Edge-to-Decision Architecture

Total-spectrum conflict means modern conflict is no longer confined to land, sea, air, and cyber. It spans civilian infrastructure, capital flows, supply chains, information networks, and narrative control. Adversaries exploit seams, undermine trust, and disrupt logistics long before kinetic operations begin.

In this paradigm, decisions depend on fresh, edge-generated events flowing across degraded networks and diverse enclaves. Monolithic ERPs concentrate risk in a single stack optimized for periodic reconciliation, not real-time decisions.

We’ve seen private-sector organizations make the pivot from centralization to composable architectures: modular services stitched together by event streams, semantic layers, and AI-enabled decision support. FedEx and UPS capture edge IoT data (location, temperature, shock) from millions of packages, stream it into enterprise analytics platforms, and expose it via APIs to predictive ETA models and customer-facing apps. Airlines stream real-time flight and crew data into decision services that decide in minutes whether to hold a flight for inbound passengers—a microservice layered on top of existing ops systems, not an ERP rewrite.

These companies assume networks will degrade, threats will persist, and requirements will evolve. They build architectures resilient and flexible enough to keep pace, building inward from edge events rather than outward from ERP systems.

This inversion is what we call Edge-to-Decision architecture: Trustworthy events are captured at the source, synchronized opportunistically, normalized via shared ontologies, and exposed as reusable services to enterprise ledgers, analytic models, and commanders.

There is no ERP system that aligns with Edge-to-Decision architecture—it requires a completely different control model for a completely different fight. While our adversaries wage total-spectrum war across our infrastructure, financial systems, and information networks, the United States and its allies remain constrained by centralized, brittle, and outdated military information systems.

The warfighter and the drone—the human being and autonomous system on the edge—generate real-time data that represents the ground source truth of the battlespace. Only when we treat information from the edge as the foundation of our military’s common operating picture will we be ready to compete with adversaries in total spectrum war.