Dutch Kindelberger, Mastermind of the Mustang

By John Fredrickson & Brian Fredrickson

John Fredrickson is an avid volunteer in his retirement and author of Warbird Factory: North American Aviation in World War II, among other books.

Lt Col Brian Fredrickson is a Program Manager in the U.S. Space Force.

North American Aviation (NAA) built over 40,000 warplanes during World War II, more than any other United States company. James Howard “Dutch” Kindelberger was the human pile driver behind this juggernaut.

Even as Allied forces battled the formidable Axis war machine in Europe and the Pacific, Kindelberger traded punches with the combat aircraft procurement cabal of U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) headquartered in Dayton, Ohio.

At stake was the legendary P-51 Mustang—an aircraft that the USAAF never intended to buy.

USAAF laid a maze of barriers and obstacles to stop the P-51. Kindelberger adroitly navigated them all. How did he do it? What lessons can be adapted to today? These questions will be answered in this week’s Heretics and Heroes.

Kindelberger traveled a twisting path before assuming the managing directorship of NAA in mid-1934. Of German ancestry, Dutch was born in 1895 into a family of soot-covered West Virginia steel workers. He dropped out of high school to join them at age 16 but shifted direction and became a student of engineering at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh. The siren-call of World War I found him as a dropout, an Army first lieutenant, a student pilot, and then an instructor pilot at Memphis.

Freshly married, Dutch separated from the military. Broke and unemployed, Kindelberger found work with the Glenn L. Martin Company in Baltimore, an incubator for the next generation of aviation entrepreneurs. Donald Douglas befriended Kindelberger at Martin and then enticed him to move west to join the fledgling Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica, CA. Their final project together was a cutting-edge airliner, the DC-2.

Dutch was hired by NAA, the aviation branch of General Motors (GM), in mid-1934. There, he used his considerable willpower and business acumen to develop some of the most iconic airplanes that ever flew. Dutch helped design the ubiquitous NAA trainer, which evolved to become the AT-6 Texan (or SNJ, as the Navy called it). In 1936, the smooth-talking Kindelberger also used his marketing skills to persuade GM’s board of directors to invest $600,000 of scarce Depression-era dollars in America’s largest and most modern airplane factory at Mines Field, now Los Angeles International Airport. His next major project was a fast-attack medium bomber, which evolved into the hard-punching B-25 Mitchell.

That lineup is impressive enough, but the most consequential project of Dutch’s career was still ahead of him.

In August 1939, with war clouds looming, the U.S. Army Air Corps (USAAC) announced a new slate of aircraft, most of which would carry the nation through the entire war. North American was awarded contracts for trainer aircraft and the B-25. To maximize warbird production, NAA was also selected to operate new plants near Kansas City and Dallas. By October 1943, the NAA workforce swelled to 91,000. An unprecedented 46% were female.

The genesis of the P-51 Mustang has been told in books and articles. Kindelberger is at the center of the story, relentlessly navigating bureaucratic obstacles to drive the plane’s rapid development, production, and deployment.

The first obstacle: U.S. and Allied military leaders wanted NAA to perpetuate the status quo via licensed production of legacy aircraft.

The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk was then considered America’s best pre-war fighter. France and England were well satisfied with their NAA trainers, so they approached Dutch Kindelberger in April 1940 to ask, “Could NAA build P-40 Warhawks on license from Curtiss?”

Kindelberger opined he did not wish to build obsolete aircraft. Others at NAA also favored a clean sheet solution, instead of taking an easy win and settling for a licensed production contract.

It was a bold move. Contracts were signed, but feathers were ruffled with top brass at Dayton. An export license was granted for the new start aircraft with the stipulation that two units be delivered to Wright Field for flight testing and evaluation.

The pursuit plane project at NAA moved at miraculous speed—an astonishing 117 days from project initiation to fabricated prototype. The prototype first flew in October 1940 under civil registration. The first plane was delivered to Wright Field in August 1941, less than two months after the U.S. Army Air Corps was renamed U.S. Army Air Forces on June 20, 1941.

Which brings us to our second obstacle: The USAAF refused to touch the P-51s.

The godfather of Army combat aircraft procurement at that time was Major General Oliver Echols (1892-1954). When NAA delivered the test articles as promised to Wright Field, Echols was still stewing over Kindelberger’s earlier insubordination.

Echols wanted NAA to build P-40 Warhawks on license from Curtiss; furthermore, Echols’ first choice for a new fighter was the Fischer P-75, a plane that, while promising on paper, was doomed from the beginning as a sinkhole for cash. Like the Great and Powerful Oz, Echols kept himself hidden behind the curtain while boosting the P-75 and strangling (via surrogates) the P-51.

Bureaucrats in Dayton slowed the limited supply of engines to NAA. Airframes without engines began piling up in the lots outside NAA’s factories. Major General Echols wanted trainers and bombers, but no more pursuit planes from NAA.

During this time, NAA test pilot Robert “Bob” Chilton traveled to Dayton. He asked to see the flight log for the P-51 model that the company had provided.

“Why has this airplane never been flown?” Chilton asked.

“Why would we waste effort flying it when there is no plan to purchase any [P-51s]?” a lieutenant responded.

So the first batch of P-51s went to Britain, not to the country of their origin.

The Brits not only named it “Mustang” but also bestowed a fresh engine, giving the plane enduring fame.

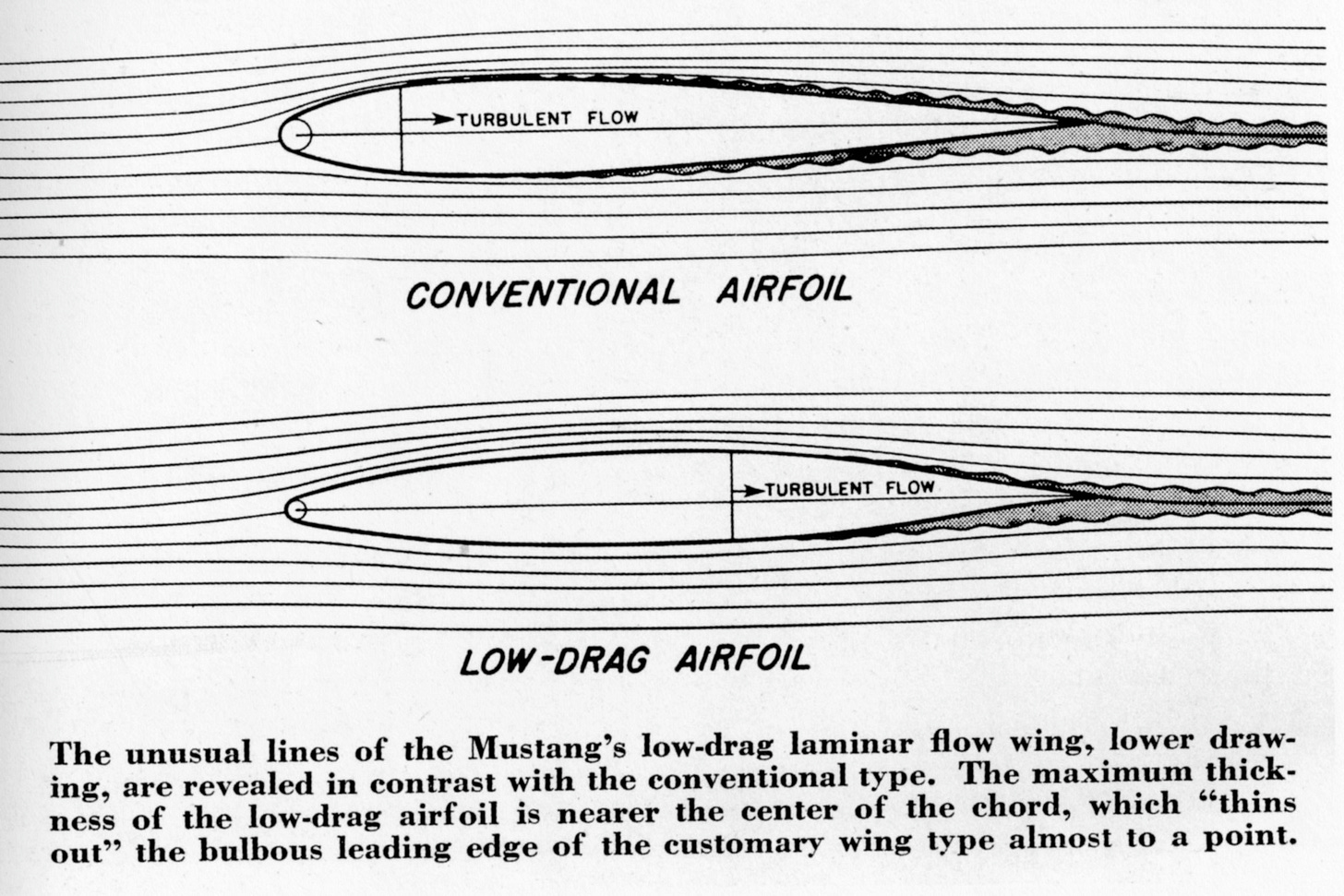

The P-51 initially used the same Model V-1710 engine that powered the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, produced by GM’s aircraft engine company, Allison. Unfortunately, the aerodynamics of the Mustang prevented installation of superchargers. Hence, Allison versions were effective only at low altitudes. It was a Rolls Royce test pilot, Ronald W. Harker, who in October 1942 first mated a Merlin engine to a Mustang airframe.

It was an instant match made in heaven.

The performance tuning of twin superchargers boosted peak performance to 25,000 feet. The breakthrough enabled the P-51 to escort and protect Allied heavy bombers, which normally cruised at and bombed from that same altitude.

Luckily for the U.S. and our Allies, NAA and Dutch Kindelberger had an ally in General Hap Arnold, who finally sliced through the procurement sludge at Dayton. Dutch and Hap were good friends as World War I pilots; they remained in frequent dialog during World War II. In August 1942, a frustrated Arnold gave the direct order and Muir Fairchild signed the letter to the Dayton bureaucrats demanding wholesale procurement of the P-51.

Arnold testified during post-war hearings that it was the only time he had intervened in the procurement process. He later stated he had no regrets regarding that decision.

Lacking fighter escorts for the longer-range missions, heavy bomber formations were taking terrible losses. The Schweinfurt-Regensburg raid of August 17, 1943, was especially brutal with the loss of 60 B-17 bombers and 600 aviators on a single mission, a rate of attrition which could not be sustained. Hap Arnold was in frantic need of a solution.

NAA opened the door for long-range missions in the form of an optional 85-gallon fuselage-mounted fuel tank for Rolls Royce equipped P-51s. Only the Mustang had the range to fly non-stop from England to Berlin, dogfight the Luftwaffe, and return to England. The combination of Allied bombers and ground attacks devastated the German homeland, which yielded V-E Day on May 8,1945.

By the end of WWII, 881 P-51s were rolling off assembly lines in Dallas and Inglewood every month. All told, NAA built 15,600 Mustangs.

The aircraft that the USAAF didn’t want is now considered by many to be the best all-around fighter of WWII.

Looking back, it’s clear that Kindelberger mustered the fortitude, tenacity, and allies to overcome Oliver Echol’s ego-imposed obstacle.

Of note, he successfully navigated:

Absence of U.S. government requirements. The Army Air Forces Material Command did not request the P-51 and refused to fly test articles in their custody. The absence of requirements gave NAA a blank sheet to conceive and maximize what was possible, rather than perpetuate legacy platforms or chase overly detailed requirements issued by well-intentioned bureaucrats with no applied design or industrial experience.

Leveraging allies and partners to make technological breakthroughs. NAA rapidly developed the P-51 under export license to France and Britain, with Britain operating the initial batch.

Not being the incumbent. When it came to nimble fighters, NAA at the time was an unproven company forging into new terrain compared to favored market leaders of the era, such as Bell, Curtiss, and Lockheed

Harnessing a leap in propulsion technology. Turns out liquid-cooled engines did work. Adapting the Packard built Rolls Royce Merlin engine was profound.

The P-51 was arguably Kindelberger’s crowning contribution to the war effort. In five consequential years from 1940-1945, the Mustang blossomed from a glint in Kindelberger’s eye to the gem of America’s Arsenal of Democracy.

But the prolonged bureaucratic battle took a toll on Kindelberger’s health. Chain smoking and drinking aggravated a struggling heart muscle, which led to his early demise at age 67. The P-51 was equally short lived. The surprise arrival of the nimble Soviet MiG-15 during the Korean War rendered prop-driven aircraft obsolete.

However, Dutch was clairvoyant. The only jet in the U.S. arsenal that could match (and sometimes best) the MiG-15 was NAA’s swept-wing beauty, the F-86 Sabre. Over 9,000 were ultimately built and they led the nation’s charge into the Jet Age, along with other great combat and experimental airplanes that followed.

Kindelberger’s legacy is a testament to Americans’ ability to collaborate in achieving breakthroughs that render previous miracles obsolete.