Barter: How Weapons Swaps Can Fix Europe’s Broken Arms Industries

A politically feasible way to boost European defense production.

Timothy Liptrot is a deployment strategist at Palantir and a PhD candidate in Political Science at Georgetown University.

The Ukraine crisis revealed a critical shortage of hardware among the armies of Europe. Despite spending $3.1 trillion on defense from 2011 to 2021, western European militaries could not give Ukraine an advantage in materiel due to low national stockpiles—and, more critically, low production. From 2004 to 2021, France, Germany, and the UK’s combined howitzers stockpile fell from 1,697 to to just 424, and Germany went from 2,400 tanks to just 339.

Europe’s defense sector is caught in a costly bind: every nation insists on protecting its own industries, even at the price of duplication and inefficiency. The result is a patchwork of small, redundant production lines that leave European militaries under-equipped and taxpayers shortchanged. Calls for open competition are ultimately naive, as they invariably unite domestic industry against reform. Instead, Europe’s militaries should establish a barter system—trading the finished products each country makes best. This approach would channel resources to the most efficient producers and deliver greater value for money while preserving the political benefits of domestic defense spending.

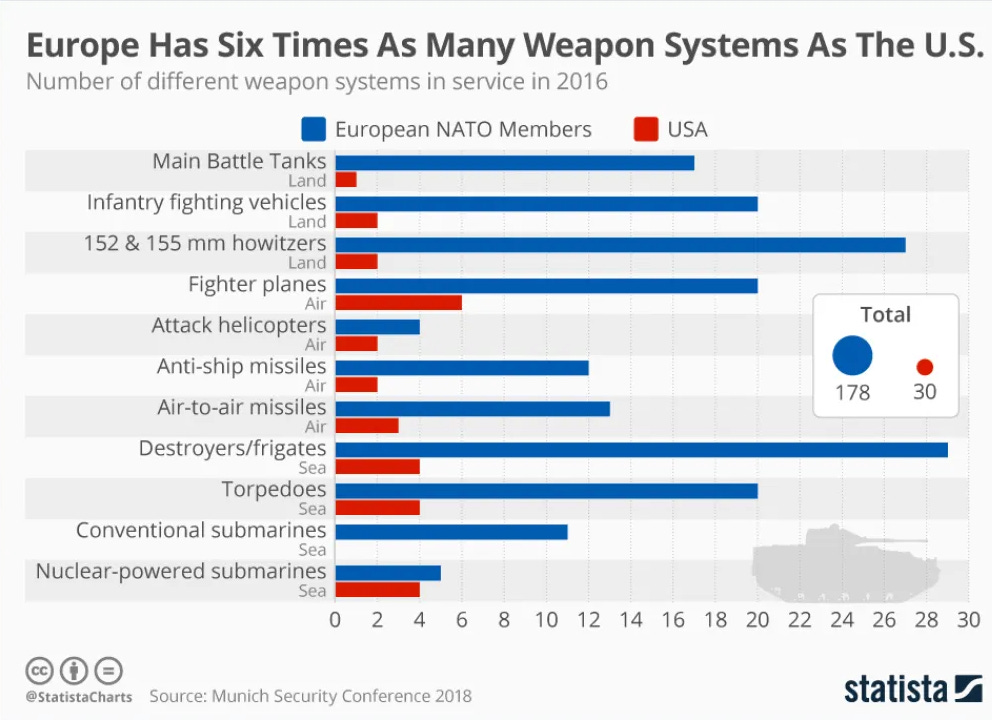

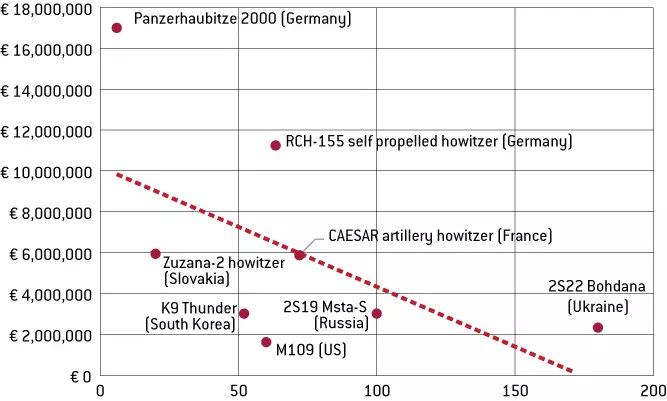

European militaries pay a high per-unit costs for their weapons systems due to a lack of national specialization and limited economies of scale. Despite Europe’s integration in other economic areas, its military industrial complexes are islands. Every major European country maintains its own primes and patronizes them almost exclusively. As a result, each country designs, builds factories for, and manufactures a different combat system of each type (except in aerospace, more on that later). Europe’s defense industrial system has tremendous redundancies in design and production to support its 17 Main Battle Tanks (MBTs), 27 howitzers, 20 fighter planes, etc.

Dispersing production across many different small firms producing a few bespoke models increases costs. Due to economies of scale, one company can produce 3,000 tanks at a lower cost than 10 companies can produce 300 tanks. The 10 companies may pay the same for steel, but they must go through 10 design processes, establish 10 factories, maintain those factories between orders, and forgo lessons from early production runs on subsequent runs. This example is not hypothetical: Italy’s only modern tank is the Ariete, which was designed entirely in Italy to produce just 200 models.

At the end of the Cold War, U.S. defense companies consolidated to adjust for the smaller demand for hardware by shrinking the number of firms and therefore increasing run size and economies of scale. We know this as the Last Supper. This process only occurred partially in Europe because European states opposed cross-border mergers of their defense companies. Once the domestic primes merge to a few medium-sized firms, consolidation stops. Leonardo Group of Italy is a typical example. It acquired many smaller Italian firms such as Agusta, Aermacchi, and Oto Melara, but acquired few and small overseas operations. Once there was nothing left to acquire in Italy, Leonardo had reached its maximum possible market share. Cross-border mergers are only common in warplanes and missiles, where the very high costs of research and development made consolidation a necessity (hence the two European multinationals, Aerobus and BAE systems).

European states can maintain an inefficient system because they control demand. Procurement officers are mostly limited to buying domestically. German procurement officers buy between 75 and 90 percent of their kit from German companies. The French military almost exclusively buys from French firms, Italy from Italian firms, and so on. The cost of maintaining all these different firms and weapon models are borne by the taxpayers, primarily by receiving fewer units (which recursively made the scale problems even worse, creating super linear declines in output from each budget cut).

Normally having many small firms would drive greater innovation, but Europe’s “each country an island” system limits that benefit. Particularly well-designed combat systems face a limited export market because their largest potential clients are forced to buy from domestic firms. The Leopard 2 tank, one of the most commercially successful European tanks, was sold to the Netherlands, Switzerland, Greece and Hungary— exclusively states too small to develop their own main battle tank.

Industrial Policy Dominance

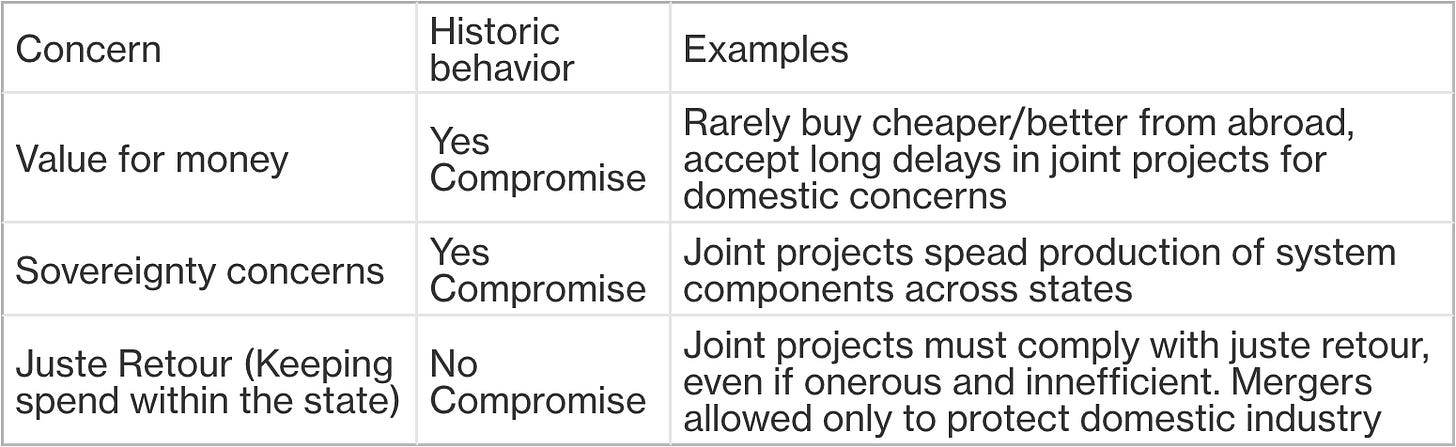

If maintaining separate military industrial bases for each of Europe’s large countries is so expensive and inefficient, why have Britain, France, Italy, and Germany chosen this path? Politicians are aware that cheaper processes exist. After all, Europe has integrated most other economic sectors. An implementable solution must satisfy the preference of key actors, in this case the politicians and procurement officers of each state. The best way to figure out those priorities is to look at the tradeoffs that states have made in their existing procurement processes (economists call these “revealed preferences”). The last section demonstrated that pure value for money is an objective on which procurement managers compromise.

National leaders sometimes cite a desire to maintain national sovereignty to justify defense autarky. A nation that depends on its neighbor for arms would face serious supply problems in a war with that neighbor. France and Germany probably do not anticipate going to war with each other today, but they might prefer to maintain independent capabilities for ideological reasons or to have independence in foreign military engagements, like the Libyan intervention.

Whatever these nations say, in practice they have been willing to compromise on this concern repeatedly. Europe’s most popular cost-control strategy for military hardware is joint projects, where multiple national companies collaborate on a product. For example, a German tank manufacturer designs and produces the tanks turret, and the French firm its chassis. Since half a tank or a third of a fighter is of limited value, these joint programs represent real compromise on the sovereign production priority. Besides, states that face a real possibility of war with their neighbors (e.g. Poland or Saudi Arabia) buy more arms from abroad, which are cheap and hard for adversaries to disrupt.

The real driver of policy is juste retour, the principle that a country’s defense spend should support domestic jobs inside that country (the term is French for "fair return", implying the real return of defense procurement is the jobs, not the weapons). Prioritizing juste retour is the revealed preference of European policymakers; they rarely compromise this objective.

Defense factories provide high-wage, high-status employment, often in politically sensitive regions. Keeping the local arms industry afloat is a reliable way to win votes and avoid angry headlines about layoffs. No politician wants the plant closed while he’s in office, so procurement officers are discouraged from buying abroad unless its absolutely necessary. Mergers might make the entire sector more efficient, but in the short term they create layoffs and loss of prestige for one party, which makes them unpopular with politicians.

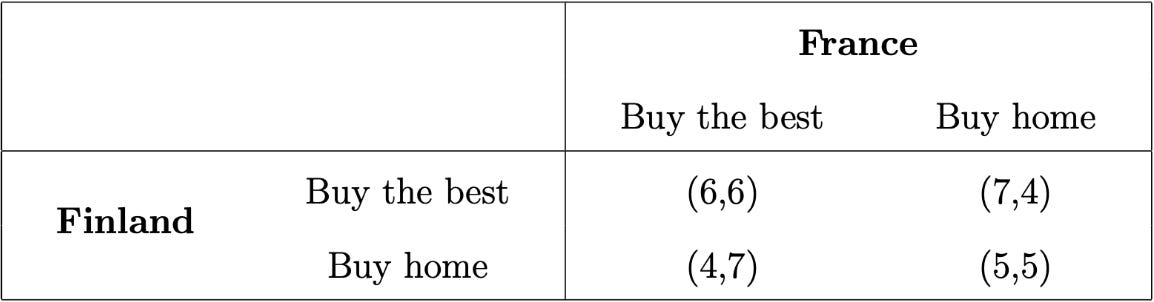

Trade between national defense industries faces a prisoners dilemma when states prioritize domestic job creation. Imagine that France and Finland both want to buy €100 million of howitzers and €100 million of armored personnel carriers (APCs). Suppose that France’s howitzer company is stronger, while Finland has a superior APC company. Each procurement officer gets one utility point for sending an order to the superior company in each product line. The procurement officers also care about jobs in their country, so they get two points for every contract awarded in their country. The outcome where each country buys the best (French howitzers and Finish APCs) gives them each six utility points (two from buying the best of each and four from spending €200 million in their state).

The outcome where both states buy the best is better for everyone than both buying at home, because the same amount is spent and quality is higher. But each individual prefers to send both contracts home, because getting a worse product is worth moving €100 million in manufacturing jobs home. Even if Finland expects France to buy from it, it still prefer to buy at home because it now gets €300 million spent at home, which is worth more than getting good quality weapons (seven utility, one from buying their good product, and six from €300 million in domestic spend). Because buying at home is always the individually superior choice, the “Buy the Best” option is not stable.

Trying to police each other into repeatedly choosing “Buy the Best” would be difficult because there is no objective standard for the “best” weapon system. Procurement officers can just change the requirement process to deny any foreign proposal.

The jobs explanation explains why cross-border mergers are rare and concentrated in aircraft. Military aircraft have exceptionally large R&D costs relative to other weapons systems, so continued separation would lead Europe to fall behind in aircraft technology. Falling behind in military plane production would have spill-over effects on European civilian aircraft, allowing the U.S. firm Boeing to pull ahead and potentially outcompete Europe’s aircraft manufacturing. By contrast, making good tanks has little effect on your ability to make cars, so mergers lack a pressing lobby.

Protecting domestic factory jobs also hobbles Europe’s other solution, the collaborative project (AKA joint venture). Under joint ventures, two nation’s firms share the total development and production costs for a new project, reducing R&D redundancies and increasing order size. The governments also get to write in very detailed juste retour clauses. Clauses require the collaboration to spend in each country as they contributed, so the jobs stay in the spending state. Because these controls constrain producers from efficiently arranging the process, they tend to result in cost overruns and much longer production timelines. This anecdote from the development of the EuroFighter Typhoon joint venture is indicative of the inefficiencies governments tolerate to ensure their money is spent at home:

Firstly, workshare requirements for the development of the Flight Control System ruled out a far cheaper technically compliant solo bid from the UK General ElectricCompany (GEC) in favour of a consortium proposal; secondly, the electronics for the Head-Up Display required UK drawings, but juste retour meant that the subsystems were produced in three different overseas locations before return to the UK for final assembly and testing; and, thirdly, Marconi, the leading UK company for systems development work, represented the only supplier possessing proven expertise and experience needed to design and produce the system, but was obliged to subcontract work to partner countries in order to meet work share percentage requirements. Worse still, in its testing role, any components Marconi failed had to be returned to the foreign originating company for rectification before re-entering the testing loop (Matthews, 2021 p. 232)

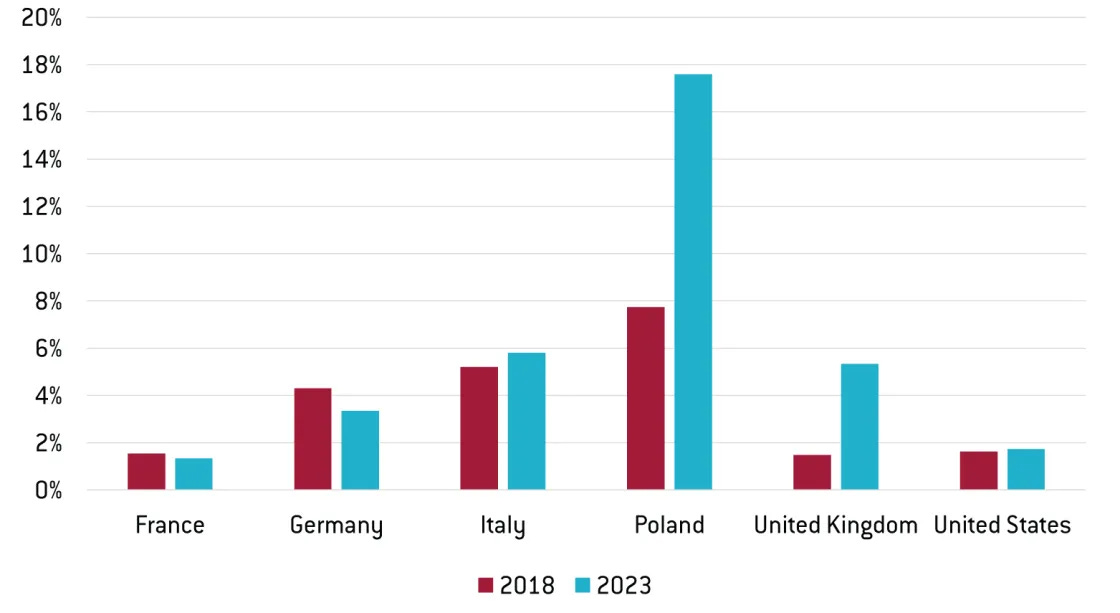

European procurement officers seem implicitly aware that they can get better value for money abroad. After the Russian invasion, European militaries increased purchases of foreign arms, particularly from the United States.

A Barter Economy for Arms

A politically viable solution must preserve the politically necessary principle of juste retour. Economists like to write articles arguing that if procurement officers just stopped caring about where the jobs are made, the system would be more efficient. That is true, but it is also unhelpful. Politicians, and the citizens they represent, will not cease valuing the benefits from keeping production within their state.

Instead of trading cash for weapons, European states should increase the trade of one weapons system for another via barter. Reconsider the example where France and Finland specialize in howitzers and APCs, respectively, and wish to trade. Suppose that instead of buying from foreign firms, the French MoD proposes a direct exchange of finished weapons. France will increase orders for domestic howitzers by €100 million if the Finns increase their APC order by €100 million, and then exchange the completed products for one another directly. Both parties would benefit from buying the better design. It would also deliver economies of scale because the resulting order sizes would be much larger.

Barter preserves the principle of juste retour without the onerous restrictions imposed on joint projects or the loss of control associated with cross-border mergers. All the Euro spent by France stay in France. This is not a mere accounting difference, because under a pure barter system the French MoD can only get more Finnish APCs if it builds more howitzers in France making French jobs. When a French procurement officer tries to purchase an Italian weapons system, the French defense industry is united against the policy. The history of European procurement suggests he will lose. But a barter trade places the most efficient firms on the procurement officer’s side, against less efficient firms, splitting the opposition.

Barter encourages specialization. France gets the most bang for its buck by producing howitzers because the other states’ MoDs value it highly, and therefore trade more of their products per Euro that France spends. It also encourages standardization across countries, which has long been a problem within NATO. Countries that produce interoperable defense products have more potential barter partners, allowing access to more efficient trades and partnerships.

There’s no need to impose a restriction that each country spend the same amount for each side of the barter exchange. In fact, it’s better that spend can be unequal. If French howitzers are particularly effective, cheap to produce, and interoperable, France should be rewarded by receiving more materiel in exchange. This encourages funding and resources to migrate from inefficient firms toward efficient firms within each country.

Firms that currently succeed in the export market, like Rheinmetal, Patria, and Nexter, would stand to gain because increasing their contracts would provide more barter value. Firms that produce expensive and marginal products would lose market share. There would be economic pain in the less efficient firms, but unfortunately that is a necessary consequence of any more efficient system. Fortunately, the employees of those firms would still enjoying a booming demand for their skills as domestic spending would stay fixed.

Barter economies have downsides. They are less flexible than free trade. Participating states must have capacity to increase production. It rewards standardization across militaries, which reduces procurement officers’ freedom to customize products. Negotiating fair exchange rates for diverse and evolving equipment could prove contentious, and delays or mismatches in production schedules might complicate timely delivery. Yet even with these limitations, a barter system offers a more politically realistic path to greater efficiency than waiting decades for a new generation of joint ventures to mature.

Implementing Barter

Since 2022, Europe has already begun experimenting with barter. Since 2022, Germany launched several “ring swap” deals with Slovakia, Greece, and Czechia to exchange German armored vehicles for kit to share with Ukraine. These deals swapped tanks or APCs Ukraine was unfamiliar with for vehicles Ukraine could use immediately. Barter of weapons for commodities is also common, like the British-Saudia Yamamah deal in the 1980s, which swapped fighter jets for oil. The problem with commodity-arms exchanges is that Britain would have bought Saudi oil anyway. An arms-for-arms barter in Europe avoids that problem because cash imports are rare.

Initial exchanges will require advance planning and trust. As a first step, two countries with low preexisting trade and mutual trust should plan a swap in advance. For example, Sweden and Norway would agree to double the production of LMGs and mortars respectively, and freeze their other line. Once each has been procured they can swap the finished goods directly. No EU regulatory change is necessary, and both parties would immediately benefit from economies of scale and better designs.

As swaps become normalized, preplanned swaps will gradually become unnecessary. Militaries routinely over-procure a few items that are particularly competitive and interoperable. Good barter products are relatively standard and interoperable, can be overproduced, and are not so high-tech that political sensitivities block a swap. 120mm mortars, Sweden’s Carl Gustaf recoilless rifles, and Belgium’s FN Scar rifles are all plausible examples (they are also systems where joint production is rare). They would then negotiate with one another to exchange their staples, allowing all to close their least efficient lines. Negotiation across the bloc will establish effective exchange rates for defense products which encourage efficiency and interoperability.

The status quo—fragmented, inefficient, and politically entrenched—has failed to deliver for Europe’s security or its taxpayers. Barter works with political realities rather than against them to offer a practical route to better value and greater capability.